Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Tuesday

Carleton classmate Mike Hazard shared with me this New York Times article about literature that unsettles us. Written by one who has written a biography about Shirley Jackson, whose short story “The Lottery” has long disturbed audiences, the piece argues that literature that disturbs and disrupts often plays a vital role in our lives. On the other hand, Ruth Franklin states that going out of one’s way not to offend is a recipe for bad writing, and she fears that “readers across the political spectrum seem to be losing their appetite for literary discomfort.”

Franklin reports that “The Lottery” discomfited when it first appeared:

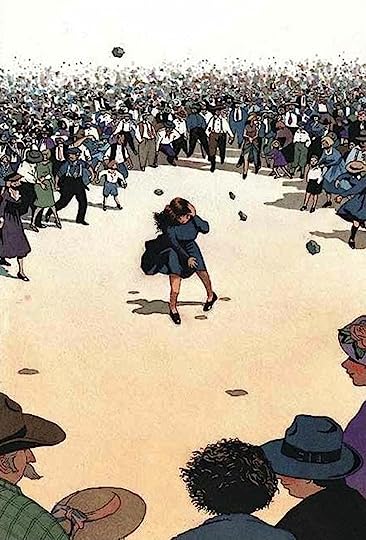

Over 150 letters flooded into The New Yorker’s offices, more mail than the magazine had ever before received for a work of fiction. Readers called the story “outrageous,” “gruesome” and “utterly pointless”; some canceled their subscriptions. I spoke to one of those readers more than a decade ago, and she still remembered, some 60 years later, how deeply the story had upset her.

Over the years, the story has been applied to various political situations, sometimes by the left, sometimes the right:

When “The Lottery” was published, three years after the end of World War II and at the start of the Cold War, many readers speculated that, given its apparent themes of conformity and cruelty, it was an allegory for McCarthyism or the Holocaust. Over the years, it has become a reliable reference when discussing some social development or troubling trend. People have heard its echo recently in the policies of Donald Trump’s MAGA populism or in the perceived excesses of the censorious mob. In Harper’s Magazine, the critic Thomas Chatterton Williams used it as a metaphor for cancel culture, which he suggested was a contemporary analogue to stoning. For the humorist Alexandra Petri, it served as the basis for a parody about the absurdities of the U.S. health care system.

This general applicability, Franklin says, derives from the story’s “unsettling open-endedness”:

Jackson deliberately declined to wrap up the ending neatly for her readers, some of whom (in a foreshadowing of the reaction to the finale of The Sopranos) asked whether The New Yorker had accidentally left out an explanatory final paragraph. That’s why it has retained its relevance across the decades: not because of any obvious message or moral, but precisely because of its unsettling open-endedness. The story works as a mirror to reflect back to its readers their current preoccupations and concerns…

While critical of the right’s book banning efforts, Franklin doesn’t let liberals off the hook. Too many, she says,

have shown a reluctance to tolerate fiction that ruffles their political sensibilities — especially in the world of young adult fiction, where several high-profile writers have canceled or delayed books dealing with subjects that have generated controversy. A few weeks ago, the best-selling author Elizabeth Gilbert decided to delay the publication of a new novel set in the mid-twentieth-century Soviet Union after online commenters, citing the conflict in Ukraine, protested that the novel sounded like it cast Russia in a romantic light.

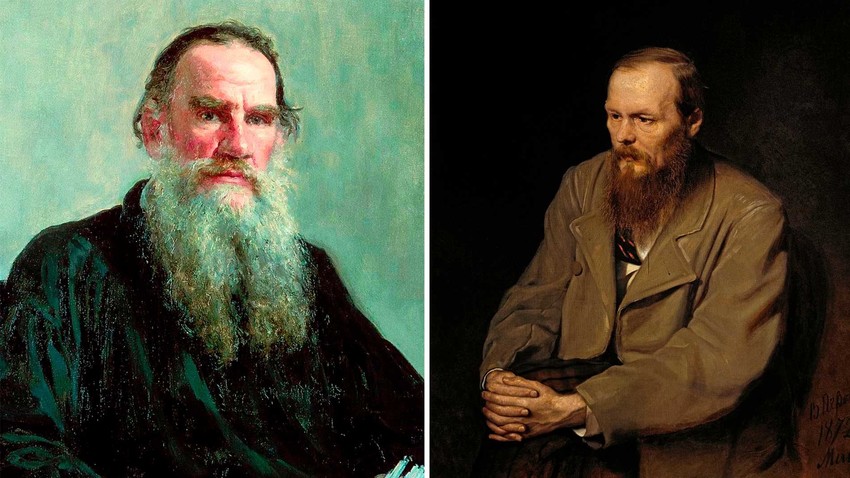

It’s worth noting that discriminating readers have long seen applying ideological litmus tests to literature as problematic, with even figures like Marx and Engels weighing in. Engels once critiqued a socialist novel for its political correctness and said that the goal of literature should be “the portrayal of real conditions.” Speaking of Balzac, a brilliant writer with royalist sympathies, Engels said that he and Marx had “learned more from him than from all the professional historians, economists, and statisticians put together.”

This is not to say that that all literature disturbs in healthy ways. There are many works that traffic in racist, sexist, and other stereotypes, with the authors going for cheap emotional effects rather than dealing with human complexity. We need to distinguish between these literary efforts (say, Thomas Dixon’s influential The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, to choose an extreme example) and those that disturb through telling truths we don’t want to hear.

I’ve been writing recently how William Faulkner, as disturbing a novelist as one will find, falls in the latter category. Nabokov’s Lolita, a novel that sometimes elicits trigger warnings in college classes for its depiction of a pedophile, discomfits in ways that I think are positive. So does Margaret Atwood’s Cat’s Eye, which upset a number feminists when it followed Handmaid’s Tale by showing that women no less than men have a dark side and are capable of great harm. In other words Atwood, who has always avoided the feminist label, was not about to sentimentalize or glorify women for the sake of a political cause. I suspect she would agree with the conclusion of Franklin’s article:

Great writing can entertain, enlighten and even empower, but one of its greatest gifts to us is its ability to unsettle, prodding us to search for our own moral in the story. “A book must be the ax for the frozen sea inside us,” Kafka once wrote. Stories like “The Lottery” create waves in that frozen sea. We stifle and censor them at our peril.

While I fully agree, I also realize that this presents English teachers with a particular challenge. It’s not easy to go up against state restrictions and repressive school boards. Far easier to teach To Kill a Mockingbird, with its sentimentalized depiction of heroic White saviors and grateful Black dependents, than Faulkner’s Light in August or Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye. But we must always keep in mind that literature is not tame, an adjective I borrow from Mr. Beaver in The Lion, the Witch, and The Wardrobe. Imagine the following description of Aslan applied to literature:

“Then he isn’t safe?” said Lucy.

“Safe?” said Mr. Beaver. “Don’t you hear what Mrs. Beaver tells you? Who said anything about safe? ‘Course he isn’t safe. But he’s good. He’s the King, I tell you.”

And later:

He’s wild, you know. Not like a tame lion.

Our students can handle literature’s wildness. More to the point, they need it. If schools only teach what they deem to be safe and tame and if publishers only publish the same, they deprive readers of the axe that is critical to our growth as human beings.