Monday

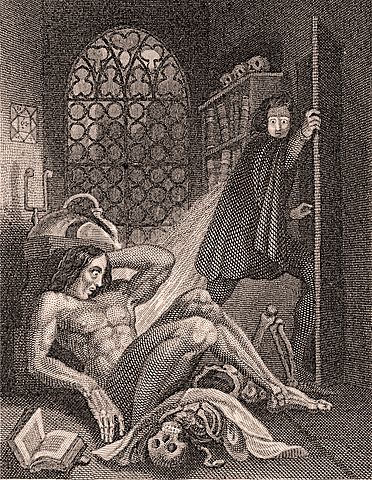

The eloquent and very smart blog Marginalian has a suggestive post on how Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein can be read as a reflection on abortion rights. To be sure, it’s not an exact fit in that Dr. Frankenstein’s decision to create or not create his “Creature” is not the same as a woman choosing to continue a pregnancy or end it. Maria Popova’s point, however, is that responsible choice is essential, and she shows how Shelley explores the ethics involved.

Incidentally, at the end of today’s post I’ve provided links to many of my own posts on the abortion debate over the years. George Eliot, Thomas Hardy, Henrik Ibsen, Maxine Hong Kingston, Lucille Clifton, John Irving, of course Margaret Atwood, and even Virgil and Jane Austen provide useful perspectives on the issue.

Popova observes that Shelley’s titanic work touches on many issues that continue to confront us today, including “artificial intelligence and genetic engineering, racism and income inequality, the longing for love and the lust for power.” The novel’s “overarching concern,” she notes, is

the responsibility of life to itself and the question of what makes a body a person; the clear sense that any life is a responsibility — one not to be taken lightly, not to be sullied with vanity and superstition, not to be used as a plaything of power (my emphasis).

Rightwing attacks on abortion have, above all, become a power play. If the so-called “right to life” movement were truly concerned about life, it would do everything in its power to support life as it comes into the world and grows into adulthood. Instead, it loses interest as soon as the child is born, as shown by its readiness to cut (or fail to fund) safety net programs for young families. As Washington Post satirist Alexandra Petri savagely puts it, “We must protect life from conception until the moment of birth!”

Why’s that? Petri explains,

Once you have been born, you are a nuisance and, possibly, a woman — two categories the Supreme Court generally frowns upon. The born are always asking for things. You want baby formula? Uncontaminated formula? You want people not to be able to bring guns to your school? You want to be mirandized? Can’t we go back to that lovely place when you were just an exciting concept who might grow up to be a Supreme Court justice?

I know some right-to-lifers say the right things, at least when they appear on National Public Television. They claim that they will work just as hard on behalf of children after they are born as they do before. This, however, is just to convince us they are humane. The actual political behavior of the GOP contradicts their ready assurances. As Peter Beinart, editor-at-large for Jewish Currents, puts it,

It’s like throwing someone from a window and then promising to build a net. Worse: It’s like doing so when ripping up nets has been your life’s work.

But back to the Marginalian essay. In Popova’s framing of Frankenstein, the scientist faces the issue all potential parents face. Shelley’s warning, Popova contends,

rises from the story sonorous and clear as larksong: Life is not to be made, unless it can be tended with love — or else it dooms all involved to a living death.

In the case of Frankenstein, because he turns his back on his creation, it becomes a murderer. As Popova puts it,

Deprived of that primary bond of love, which moors us to the seabed of being to weather life’s storms, the Creature…is savaged by such profound self-loathing that he ends up destroying numerous innocent passersby who cross his sad path. “I am malicious because I am miserable,” he roars in one the truest and most devastating lines in all of literature, in all the common record of our reckoning with human nature.

Many women who unexpectedly find themselves pregnant grapple with whether it is more responsible to continue with their pregnancy or to end it. Some decide one way, some another, and no universal governmental policy can begin to approach all the factors and all the struggle involved in their decision. That is why, for the past 50 years, we have let them choose. We advise them to confer with their doctors and the wise people around them but, in the end, it is they who are putting their bodies on the line and so they who must make the call.

While Popova treats Victor Frankenstein as the father, her argument works better if he is seen as those who force a woman to have a child against her will—and who then wash their hands of all responsibility for what happens to mother and child. Think of them as akin to absentee fathers. As Popova puts it, “Unable to love the life he has made, [Frankenstein] fails to rise to the fundamental responsibility that parenting demands.”

Instead, having created a life “out of vainglorious ambition and existential loneliness,” he “flees from his own creation in horror.” Here’s the moment from the novel:

[The Creature’s] jaws opened, and he muttered some inarticulate sounds, while a grin wrinkled his cheeks. He might have spoken, but I did not hear; one hand was stretched out, seemingly to detain me, but I escaped and rushed downstairs. I took refuge in the courtyard belonging to the house which I inhabited, where I remained during the rest of the night, walking up and down in the greatest agitation, listening attentively, catching and fearing each sound as if it were to announce the approach of the demoniacal corpse to which I had so miserably given life.

Later, when the Creature disappears from the scene, Frankenstein believes he has escaped all consequences:

I threw the door forcibly open, as children are accustomed to do when they expect a spectre to stand in waiting for them on the other side; but nothing appeared. I stepped fearfully in: the apartment was empty, and my bedroom was also freed from its hideous guest. I could hardly believe that so great a good fortune could have befallen me, but when I became assured that my enemy had indeed fled, I clapped my hands for joy and ran down to Clerval.

Of course, there are consequences. Now that Roe v Wade has been overturned, will the right-to-life people take responsibility for women who become gravely ill or even die because doctors, fearing the law, are reluctant to perform timely abortions? Will they deal fully with the emotional scars of women and children who give birth to their rapists’ children—or even to children they don’t want or are not ready for? Will they take responsibility for the poverty that might otherwise have been avoided had a woman or a couple chosen to abort? Or will they run out of the room, clap their hands for joy, and then pretend that the problem has taken care of itself.

Frankenstein, at least, takes responsibility. As he puts it,

In a fit of enthusiastic madness I created a rational creature and was bound towards him to assure, as far as was in my power, his happiness and well-being.

If the right-to-life movement were truly interested in life, it would do all in its power to support women and children in poverty, to ensure mandated and paid maternity leave, to guarantee universal health care so that the United States would not lead (by a long shot) all developed nations in infant mortality.

But “right to life” has never been about life because this country’s rightwing is not interested in life, as indicated by their opposition to gun safety and vaccinations and police accountability and their support for the death penalty. Life for these people, as it is initially for Victor Frankenstein, is to be used as a plaything for power.

Until their actions demonstrate otherwise, ignore their protestations to the contrary.

Previous Posts about Abortion Issues (in reverse chronological order)

They Really Are Coming for Your Body (May 15, 2022)

Appeasement doesn’t stop bullies, and having overturned Roe v Wade will not stop the right from going after other rights. Margaret Atwood understands this.

Handmaid’s Tale Comes a Step Closer to Reality (May 3, 2022)

We’re a step closer to The Handmaid’s Tale. But can find strength from A Wrinkle in Time.

A Texas Pol Attacks Cider House Rules (Oct. 31, 2021)

A Texas legislator wants to ban Cider House Rules, which has a sensitive exploration of abortion. This is no surprise.

On Grendel, a Boston Bar, and a Texas Law (Sept. 12, 2021)

A case involving a Boston bar (Grendel’s Den) may be invoked in legal challenges to the new Texas abortion ban. What would Beowulf do?

Atwood, Austen, and Texas’s Bounty Abortion Law (Sept. 6, 2021)

Texas’s new abortion law, which incentives citizens to snitch on their neighbors, brings to mind Handmaid’s Tale, 1984, and Northanger Abbey.

Think of Amy Coney Barrett as Aunt Lydia (Oct. 13, 2020)

Given Amy Comey Barrett’s rightwing positions on abortion, healthcare, and LGBTQ rights, she can be compared to Aunt Lydia in Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale.

The Christian Right’s Faustian Bargain (July 6, 2019)

A recent Atlantic article provides a compelling explanation for why rightwing evangelicals love Trump: feeling embattled, they have traded core principles for power. Like Doctor Faustus.

Camilla, the Woman Who Fights Back (Oct. 1, 2018)

Camilla is a woman who fights back against Aeneas. It proves to be all in vain, which may be the case of those opposing rightwing justices on the Supreme Court.

How Atwood Rescued This Single Mom (Jan. 22, 2018)

In an inspiring story, single mom Ashley found Atwood’s novels helped her turn her life around.

Handmaid’s Tale, More Relevant Than Ever (April 26, 2017)

With Hulu set to release Handmaid’s Tale tomorrow, I gather together all my past posts on Atwood’s dystopian classic. The novel isn’t only important for liberals but has lessons for rightwing women as well.

Fundamentalists Send Readers to Atwood (Feb. 19, 2017)

Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale is topping bestseller lists at the moment. The reason is probably because of the GOP’s prospect of success in curbing reproductive freedom.

Trump, Macduff, and “Untimely Ripped” (Oct. 25, 2016)

Donald Trump’s characterization of late-term abortions as “ripping” harken back to a verb used in Macbeth. Most people, however, would argue that both Trump and Macduff are describing caesarians.

Sans Scalia, a Happy Midsummer Ending? (March 3, 2016)

The late Antonin Scalia claimed to be a strict textualist and would have found some excuse to support Texas’s law designed to close down abortion centers. There’s a Scalia-type character in Midsummer Night’s Dream. Fortunately, by the end of the play he has been overruled.

Unwanted Pregnancies, Desperate Women (Nov. 22, 2015)

As reproductive service centers are closed down by conservative state legislatures, attempted self abortions are on the rise. For a literary depiction of a desperate woman there is Hetty Sorrel from George Eliot’s Adam Bede.

Lucille Clifton on Abortion and Respecting Women (Sept. 30, 2015)

Shock strategies by anti-abortionists may work on Congress but are less likely to work on women. As the body poems of Lucille Clifton demonstrate, women already know much more about their bodies than Congressmen do.

The Abortion Debate and Doll’s House (Sept. 21, 2015)

Our society’s impasse over abortion is like the impasse in Ibsen’s Doll’s House between Thorvald and Nora: he insists on moral absolutes, she resents being infantilized.

Queasy about Bodies Used for Medicine (Aug.4, 2015)

The sting videos by anti-abortion activists are designed to shock. But being shocked by the use of dead bodies for medical research is nothing new, as seen in the grave robbing scene in Tom Sawyer.

Teaching Gender Sensitivity at West Point (Feb. 18, 2015)

Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale is required reading for entering West Point cadets. Good things could happen.

Kingston’s No Name Woman vs. Anti-Abortionists (Jan. 28, 2015)

Maxine Hong Kingston’s “No Name Woman” works as a powerful response to those attempting to distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate rape.

Imagine Austen vs. War on Women (Sept. 30, 2014)

Rightwing attacks on reproductive rights have antecedents in the moralistic judgments of Mr. Collins and Mary Bennet in Pride and Prejudice.

Female Freedom Drives Right Crazy (March 24, 2014)

Euripides The Bacchae well describes rightwing legislators obsessed with abortion.

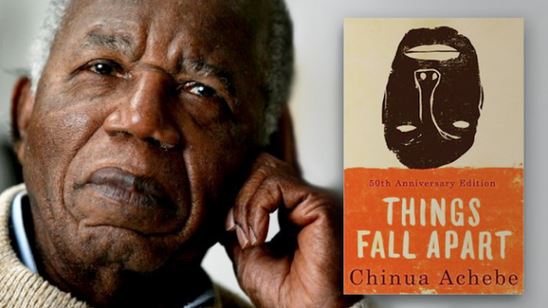

Things Fall Apart in Bishops vs. Nuns (Oct. 4, 2013)

Achebe’s Things Fall Apart contrasts rigid and tolerant Christianity in ways that will benefit our own society.

A 17th Century Comedy Addressing Rape (March 15, 2013)

The Right Wing’s “war on women” is affecting the way my students read Aphra Behn.

John Irving’s Defense of Abortion (Oct. 3, 2012)

Cider House Rules calls out those anti-abortion proponents who refuse to face up to the lengths to which some desperate women are willing to go.

How Right Wing Would Respond to Tess (Sept. 17, 2021)

Tess of the D’Urbervilles puts a human face on the dilemmas of rape victims. Romney/Ryan, take note.

Ryan, Abortion, and Hardy’s Angel Clair (Aug. 15, 2012)

Paul Ryan may resemble Angel Claire in Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles, but there’s a vicar in the novel who shows us a better way of dealing with a “fallen” woman.