Wednesday

My librarian friend Valerie Hotchkiss alerted me to an article by Professor Misty Krueger recommending Jane Austen for people undergoing stress. The purported subject is how those suffering from the Covid pandemic will benefit from reading or rereading the novels, but it also touches on how those traumatized by war and by cancer have turned to her. Given that the article sprawls in these many directions, I’ll just note some of the highlights here. For instance, there this:

Austen’s plots provide a welcome escape from reality while also helping us both better understand ourselves and the people in our lives and handle as best we can what life throws at us. During the pandemic, for example, many people have spent too much time isolated from family, friends, coworkers, and even potential companions; for others the pandemic forced us to spend more time with our loved ones than perhaps we ever imagined or wanted. Whether we felt isolated from other people or even from our own active selves or felt the desire to escape our remote, stay-at-home routines, turning to Austen during this difficult time made it easier to process the effects of the pandemic on our lives and, through this universalizing experience, to empathize with Austen’s characters as well as fans across the globe.

Krueger and I were on the same wavelength here since, after reading this, I instantly thought of Rudyard Kipling’s short story “The Janeites,” which she turns to as well. The Janeites are a club in the World War I trenches who find solace in Austen’s novels. One of them recommends “Jane when you’re in a tight place.”

Krueger says that Jane Austen therapy has not been confined to fiction:

Doctors prescribed Austen’s novels to soldiers during and after World War I due to what Claudia Johnson calls the “rehabilitative” nature of Austen’s writings on “shattered minds,” and what [Mary] Favret likens to “restorative therapy.” Lee Siegel too writes of “shell-shocked veterans” who “were advised to read Austen’s novels for therapy, perhaps to restore their faith in a world that had been blown apart while at the same time respecting their sense of the world’s fragility.”

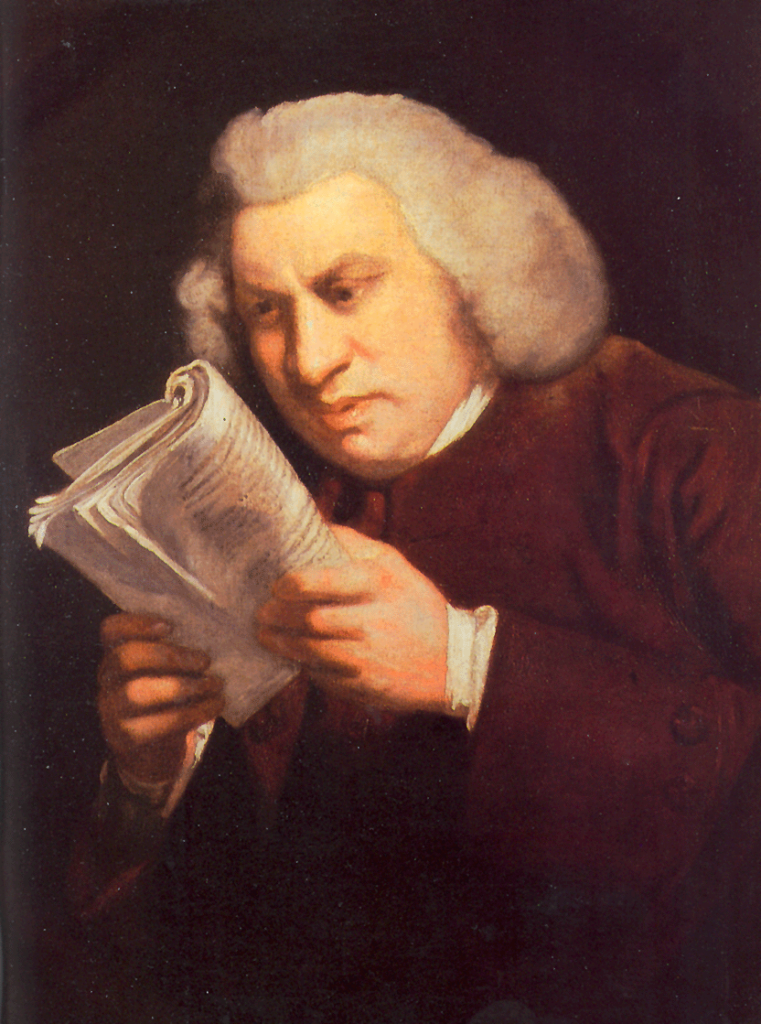

Austen also played a role during World War II. For instance, Winston Churchill, when he was recovering from pneumonia in 1943, turned to Austen:

Austen helped Churchill regain his sense of self. He states that in his convalescence he felt disconnected from himself: “it was like being transported out of oneself.” In his recovery he was instructed not to work or worry, so he “decided to read a novel” (actually, to have his daughter read one to him): Pride and Prejudice. Churchill enjoyed the “calm lives” of Austen’s characters and saw them as free from the stresses of war and living in a world for which the biggest problems concerned “manners” and “natural passions.”

Nor was Churchill alone, as Professor Favret notes in another article:

Other individuals wrote to the literary journals to report that they too were reading—and re-reading—Austen’s novels, often at a terrific rate. War years in England provoked an energetic discussion of the merits of re-reading; and though she wasn’t the only re-read author, Jane Austen always figured in the discussion. There was an assumption at the time that re-reading books from Britain’s tremendous literary past served as fortification against the upheavals of wartime. Austen provided something additional, at least in the eyes of British novelist Rebecca West: her work demonstrated an “underlying faith that the survival of society was more essential to the moral purpose of the universe than the survival of the individual,” and such faith could prove crucial in wartime. The public re-read Austen in particular, writes a London paper in 1943, because “Her books are full of the drowsy hummings of a summer garden, which can deafen ears even to the hummings of the aeroplane overhead.”

Krueger says that reading Austen helps build up our resilience. Reading the novelist, she notes, can be a form of what Mayo Clinic researchers have called “self-directed stress management,” helping patients “divert negative thoughts and interpret experiences positively.” Although the clinic doesn’t mention reading Austen, Krueger says that her novels can help us survive “months of uncertainty and social isolation”:

Austen’s world…holds up a mirror to ours, and people have identified with her characters’ life-threatening maladies, quarantines, and social distancing. It seems that we share the troubles faced by Marianne Dashwood, Jane Bennet, Tom Bertram, Harriet Smith, Louisa Musgrove, and more; some of us might even identify with hypochondriacs Mr. Woodhouse and the Parkers as we panic about coronavirus. If Austen’s characters can survive sickness and seclusion with grace, surely we can too. Right? One of the things we admire about Austen’s characters, Janice Hadlow reminds us, is their resilience.

Later in her piece, Krueger mentions the “Jane Austen Guide for Surviving Covid,” which I believe I’ve blogged on in the past. Created during the lockdown days of the virus by Megan O’Keefe, it recommends

only leaving the house to take long walks and “essential trips”; “suddenly wearing gloves, writing letters to far away friends, and taking on unique hobbies”; “maintain[ing] a respectable distance of at least six feet” while in public; and skipping large gatherings like parties (or balls)—to our own pandemic habits.

Krueger also mentions Josephine Tovey’s article “Sense and Social Distancing: Lockdown Has Given Me a Newfound Affinity with Jane Austen’s Heroines”:

The article recalls the absurdity-cum-reality of the scene in Pride and Prejudice when Caroline Bingley encourages Elizabeth Bennet “‘to follow [her] example, and take a turn about the room’” because it is “‘refreshing.’” Tovey “discovered a newfound sympathy—affinity even—for every character battling tedium in that room.” Surely, many of us can relate: “All of a sudden, period dramas have become extremely relatable. Ceaseless hours indoors with your family? Fretting about falling into financial ruin? Feeling an outsized thrill at a neighbor who stops by to visit? There’s an Austen for that.” Tovey speaks to the “inherent suffocation of a life lived almost entirely within the same four walls” and how our experiences in pandemic lockdown are providing us with a “fresh appreciation for why characters like Elizabeth Bennet and . . . Marianne Dashwood find a simple walk so electrifying. It gives them freedom and perspective.”

In short, you can find better living through Jane Austen. For an author whose first work appear in 1811 and who died six novels and six years later, she’s had a hell of an impact.