Thursday

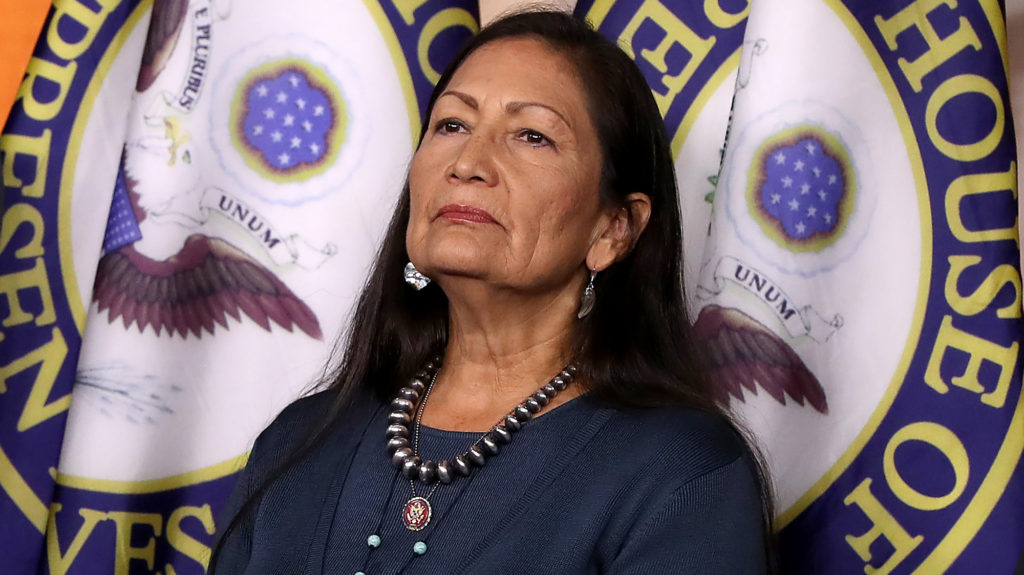

I’m using today’s post to brainstorm about a chapter I’m writing in my book Does Literature Makes Us Better People? On the question of whether “lightweight literature” is good or bad for us, I reflect upon Jane Austen’s thoughts in Northanger Abbey about Anne Radcliffe’s gothic fiction. Whatever Radcliffe’s contribution to the gothic, she is no Jane Austen.

There probably was a time in her life when Austen actively explored whether she should take a Radcliffe route with her own fiction. After all, gothic fiction made Radcliffe rich and famous, two things Austen would very much have liked for herself. Northanger Abbey indicates, however, that Austen found the gothic too confining for the issues she wanted to explore.

She may, however, have captured her own youthful enthusiasm for Radcliffe’s gothics through Catherine’s love of them. Among other things, gothics provided opportunities for friendship bonding, just as works like Harry Potter, Twilight, and The Hunger Games do today. In one passage, we see Catherine and her best friend Isabella Thorpe sharing their enthusiasm:

But, my dearest Catherine, what have you been doing with yourself all this morning? Have you gone on with Udolpho?”

“Yes, I have been reading it ever since I woke; and I am got to the black veil.”

“Are you, indeed? How delightful! Oh! I would not tell you what is behind the black veil for the world! Are not you wild to know?”

“Oh! Yes, quite; what can it be? But do not tell me—I would not be told upon any account. I know it must be a skeleton, I am sure it is Laurentina’s skeleton. Oh! I am delighted with the book! I should like to spend my whole life in reading it. I assure you, if it had not been to meet you, I would not have come away from it for all the world.”

“Dear creature! How much I am obliged to you; and when you have finished Udolpho, we will read the Italian together; and I have made out a list of ten or twelve more of the same kind for you.”

“Have you, indeed! How glad I am! What are they all?”

“I will read you their names directly; here they are, in my pocketbook. Castle of Wolfenbach, Clermont, Mysterious Warnings, Necromancer of the Black Forest, Midnight Bell, Orphan of the Rhine, and Horrid Mysteries. Those will last us some time.”

“Yes, pretty well; but are they all horrid, are you sure they are all horrid?”

“Yes, quite sure…

As she reflects on the immense popularity of novels, Austen must battle against the notion that all novels are lightweight, not just the lightweight ones. “Although our productions have afforded more extensive and unaffected pleasure than those of any other literary corporation in the world,” she complains, “no species of composition has been so much decried.” What passes for serious reading, she points out, has far less creativity to it:

And while the abilities of the nine-hundredth abridger of the History of England, or of the man who collects and publishes in a volume some dozen lines of Milton, Pope, and Prior, with a paper from the Spectator, and a chapter from Sterne, are eulogized by a thousand pens—there seems almost a general wish of decrying the capacity and undervaluing the labor of the novelist, and of slighting the performances which have only genius, wit, and taste to recommend them.

The same goes for Addison and Steele’s Addison and Steele’s Spectator essays, which by the time Austen wrote Northanger Abbey would have been almost a century old:

Now, had the same young lady been engaged with a volume of the Spectator, instead of such a work, how proudly would she have produced the book, and told its name; though the chances must be against her being occupied by any part of that voluminous publication, of which either the matter or manner would not disgust a young person of taste: the substance of its papers so often consisting in the statement of improbable circumstances, unnatural characters, and topics of conversation which no longer concern anyone living; and their language, too, frequently so coarse as to give no very favorable idea of the age that could endure it.

Elsewhere in the passage Austen holds up Fanny Burney’s Cecilia and Camilla and Maria Edgeworth’s Belinda as models of what the novel is capable of:

“I am no novel-reader—I seldom look into novels—Do not imagine that I often read novels—It is really very well for a novel.” Such is the common cant. “And what are you reading, Miss—?” “Oh! It is only a novel!” replies the young lady, while she lays down her book with affected indifference, or momentary shame. “It is only Cecilia, or Camilla, or Belinda”; or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humor, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language.

Yet for all her defense of novels, Austen sees some problems with Radcliffe. After all, they lead Catherine to believe that General Tilney has either killed his wife or locked her away. This leads to Henry Tilney’s painful rebuke, which ends with Catherine running away in tears:

If I understand you rightly, you had formed a surmise of such horror as I have hardly words to—Dear Miss Morland, consider the dreadful nature of the suspicions you have entertained. What have you been judging from?

A number of feminist critics have come to Catherine’s defense, noting that gothic novels haven’t totally misled her. General Tilney may not have locked in wife in a dungeon, but she has in fact been trapped in an unhappy marriage with a tyrannical man. Feminist Tania Modleski, in Loving with a Vengeance: Mass Produced Fantasies by Women, notes that paranoia is at the heart of the gothic and that paranoia grows out of extreme power imbalance:

In his massive study on The Paranoid Process, William Meissner claims that the paranoid usually comes from a family whose power structure is greatly skewed: one of the parents is perceived as omnipotent and domineering, while the other is perceived (and most usually perceives him/herself) as submissive to and victimized by the stronger partner…

Gothic novels, Modleski explains, give expression

to women’s hostility towards men while simultaneously allowing them to repudiate it. Because the male appears to be the outrageous persecutor, the reader can allow herself a measure of anger against him; yet at the same time she can identify with a heroine who is entirely without malice and innocent of any wrongdoing.

Throughout Northanger Abbey, Catherine is periodically made aware of her relative lack of power. At one point, in a parody of a gothic abduction, she is carried off against her will by the wannabe rake John Thorpe. She sees how General Tilney domineers over Henry and his sister and suffers herself when he expels her from Northanger Abbey with no explanation given. Of the literature readily available to her, the gothic does a pretty good job of capturing her sense of vulnerability.

But does it do as good a job as Jane Austen’s novels would? Over and over we see Austen women negotiating their vulnerability in patriarchal society—the Dashwood sisters in Sense and Sensibility, the Bennett sisters in Pride and Prejudice, Fanny Price in Mansfield Park, Anne Elliot in Persuasion. If Catherine needs a guide for the world in which she lives, wouldn’t these novels serve her better?

Charming as were all Mrs. Radcliffe’s works, and charming even as were the works of all her imitators, it was not in them perhaps that human nature, at least in the Midland counties of England, was to be looked for. Of the Alps and Pyrenees, with their pine forests and their vices, they might give a faithful delineation; and Italy, Switzerland, and the south of France might be as fruitful in horrors as they were there represented. Catherine dared not doubt beyond her own country, and even of that, if hard pressed, would have yielded the northern and western extremities. But in the central part of England there was surely some security for the existence even of a wife not beloved, in the laws of the land, and the manners of the age. Murder was not tolerated, servants were not slaves, and neither poison nor sleeping potions to be procured, like rhubarb, from every druggist. Among the Alps and Pyrenees, perhaps, there were no mixed characters. There, such as were not as spotless as an angel might have the dispositions of a fiend. But in England it was not so; among the English, she believed, in their hearts and habits, there was a general though unequal mixture of good and bad. Upon this conviction, she would not be surprised if even in Henry and Eleanor Tilney, some slight imperfection might hereafter appear; and upon this conviction she need not fear to acknowledge some actual specks in the character of their father, who, though cleared from the grossly injurious suspicions which she must ever blush to have entertained, she did believe, upon serious consideration, to be not perfectly amiable.

Although the Austen novels that Catherine needs haven’t been written yet, there are others available, most notably the works of Samuel Richardson, whom Austen admired. While Isabella Thorpe shudders at the thought of Richardson, Catherine is open to Sir Charles Grandison, perhaps Austen’s favorite novel. Isabella begins:

“It is so odd to me, that you should never have read Udolpho before; but I suppose Mrs. Morland objects to novels.”

“No, she does not. She very often reads Sir Charles Grandison herself; but new books do not fall in our way.”

“Sir Charles Grandison! That is an amazing horrid book, is it not? I remember Miss Andrews could not get through the first volume.”

“It is not like Udolpho at all; but yet I think it is very entertaining.”

“Do you indeed! You surprise me; I thought it had not been readable.

Charles Grandison was Richardson’s response to Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones, which Samuel Johnson accused of leading young men astray by making vice seem attractive. Austen appears to agree with Johnson and makes Tom Jones the favorite novel of Isabella’s doltish brother, who undoubtedly enjoys Tom’s drinking and womanizing. Grandison, by contrast, is a sensitive and noble man who saves the abducted heroine and then refuses a duel challenge from her captor because of his moral objections to dueling. Henry Tilney, resembling Grandison rather than Tom Jones, represents a new kind of man.

Evidence of this is his enjoyment of novels. If real men in our own age like quiche, then real men for Jane Austen understand muslin (as Tilney does in an earlier scene) and aren’t afraid to openly love Radcliffe novels. Catherine begins the conversation:

“But you never read novels, I dare say?”

“Why not?”

“Because they are not clever enough for you—gentlemen read better books.”

“The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid. I have read all Mrs. Radcliffe’s works, and most of them with great pleasure. The Mysteries of Udolpho, when I had once begun it, I could not lay down again; I remember finishing it in two days—my hair standing on end the whole time.”

All of which to say is that Austen believes that, while good novels can do good in the world, lightweight novels (into which category she would include Tom Jones as well as Mysteries of Udolpho) can do harm. It’s all very well if one can see them for what they are, as Tilney does. But for a superior understanding, one needs a Richardson or a Burney.

Or an Austen.

Further thought: Throughout her novels Austen shows herself cautious about literature that emotionally carries the reader away. In Sense and Sensibility, Marianne and Willoughby bond over the passionate poetry of William Cowper and the historical romances of Sir Walter Scott while admiring “no more than is proper” the poetry of Alexander Pope, which balances passion with reason (as in Essay on Man). The Bertrams and Crawfords lose themselves in the illicit relationships of Elizabeth Inchbald’s Lovers’ Vows in Mansfield Park and, by the end of the novel, Henry and Maria have broken society’s rules. Meanwhile, Captain Benwick and Louisa Musgrove prove they have less substance than Captain Wentworth and Anne Elliot when they bond over Scott’s Lady of the Lake and Marmion and Lord Byron’s Giaour and The Bride of Abydos. Talking to Benwick, Anne discovers that he is

intimately acquainted with all the tenderest songs of the one poet, and all the impassioned descriptions of hopeless agony of the other; he repeated, with such tremulous feeling, the various lines which imaged a broken heart, or a mind destroyed by wretchedness, and looked so entirely as if he meant to be understood, that she ventured to hope he did not always read only poetry, and to say, that she thought it was the misfortune of poetry to be seldom safely enjoyed by those who enjoyed it completely; and that the strong feelings which alone could estimate it truly were the very feelings which ought to taste it but sparingly.

At least Scott and Byron contributed to her own happiness, however. They lure Louisa away from Wentworth, leaving him free to marry Anne:

She saw no reason against their being happy. Louisa had fine naval fervor to begin with, and they would soon grow more alike. He would gain cheerfulness, and she would learn to be an enthusiast for Scott and Lord Byron; nay, that was probably learnt already; of course they had fallen in love over poetry. The idea of Louisa Musgrove turned into a person of literary taste, and sentimental reflection was amusing, but she had no doubt of its being so.

To cite one other instance of literature’s dangers, wannabe rake Sir Edward Denham in Sanditon uses poetry to seduce, prizing above all the “illimitable ardor” of Robert Burns:

If ever there was a man who felt, it was Burns. Montgomery has all the fire of poetry, Wordsworth has the true soul of it, Campbell in his pleasures of hope has touched the extreme of our sensations—’Like angel’s visits, few and far between.’ Can you conceive anything more subduing, more melting, more fraught with the deep sublime than that line? But Burns—I confess my sense of his pre-eminence, Miss Heywood. If Scott has a fault, it is the want of passion. Tender, elegant, descriptive but tame. The man who cannot do justice to the attributes of woman is my contempt. Sometimes indeed a flash of feeling seems to irradiate him, as in the lines we were speaking of—’Oh. Woman in our hours of ease’—. But Burns is always on fire. His soul was the altar in which lovely woman sat enshrined, his spirit truly breathed the immortal incense which is her due.”

Charlotte doesn’t dispute the spirit but is suspicious of Burns’s promiscuity:

“I have read several of Burns’s poems with great delight,” said Charlotte as soon as she had time to speak. “But I am not poetic enough to separate a man’s poetry entirely from his character; and poor Burns’s known irregularities greatly interrupt my enjoyment of his lines. I have difficulty in depending on the truth of his feelings as a lover. I have not faith in the sincerity of the affections of a man of his description. He felt and he wrote and he forgot.

While literature’s ability to arouse the passions is good, it becomes dangerous when it jettisons reason and morality. Again, Austen offers a healthy balance.