Monday

The search for meaning becomes urgent in times of crisis, and for much of history this search has occurred within a religious context. Although many started looking for secular answers following the scientific revolution, the search itself has remained constant. By surveying literature’s handling of the plague over the centuries, we get some perspective on our own search for meaning.

Sophocles’s Oedipus sends his brother-in-law to the Delphic Oracle to inquire about the cause of a plague that has struck Thebes. It so happens that the gods are punishing the city because Oedipus has unknowingly violated foundational taboos. To end the plague, the contamination must be expelled.

The plague that shows up in The Aeneid (29-19 BCE) alerts Aeneas that he and his father have misinterpreted an oracle. They thought they were to begin their new enterprise in Crete, but in fact they should plant their flag in Italy. The plague therefore sends them to sea again:

Our ships were no sooner hauled

onto dry land, our young crewmen busy with weddings,

plowing the fresh soil while I was drafting laws

and assigning homes, when suddenly, no warning,

out of some foul polluted quarter of the skies

a plague struck now, a heartrending scourge

attacking our bodies, rotting trees and crops,

one whole year of death . . .

Men surrendered their own sweet lives

or dragged their decrepit bodies on and on.

And the Dog Star scorched the green fields barren,

the grasses shriveled, blighted crops refused us food.

In both these instances, there’s something that can be done to defeat the plague: bring your lives more in alignment with divine will.

For Defoe, as I discussed yesterday, the plague is also believed to be sending messages. As a Puritan, the narrator of Journal of the Plague Year (1722) blames it on Charles II’s licentious reign, which was a reaction to England’s 18-year experiment with a Puritan republic. The plague, he observes, gets Charles’s Court to clean up its act (albeit only temporarily):

[T]he very Court, which was then gay and luxurious, put on a face of just concern for the public danger. All the plays and interludes which, after the manner of the French Court, had been set up, and began to increase among us, were forbid to act; the gaming-tables, public dancing-rooms, and music-houses, which multiplied and began to debauch the manners of the people, were shut up and suppressed; and the jack-puddings, merry-andrews, puppet-shows, rope-dancers, and such-like doings, which had bewitched the poor common people, shut up their shops, finding indeed no trade; for the minds of the people were agitated with other things, and a kind of sadness and horror at these things sat upon the countenances even of the common people. Death was before their eyes, and everybody began to think of their graves, not of mirth and diversions.

While narrator H.F. is convinced that God is sending messages, however, some scientific thinking has also crept into his world view. Therefore, he’s skeptical that a comet foretold the plague:

I saw both these stars, and, I must confess, had so much of the common notion of such things in my head, that I was apt to look upon them as the forerunners and warnings of God’s judgements; and especially when, after the plague had followed the first, I yet saw another of the like kind, I could not but say God had not yet sufficiently scourged the city.

But I could not at the same time carry these things to the height that others did, knowing, too, that natural causes are assigned by the astronomers for such things, and that their motions and even their revolutions are calculated, or pretended to be calculated, so that they cannot be so perfectly called the forerunners or foretellers, much less the procurers, of such events as pestilence, war, fire, and the like.

Then H.F. encounters the same problem Aeneas does: even when God sends warnings, it’s not clear how we should respond. For instance, he is in a quandary whether he should trust in God and stay in London or trust in God to look after his possessions while he leaves. He sees it one way, his brother another:

It immediately followed in my thoughts, that if it really was from God that I should stay, He was able effectually to preserve me in the midst of all the death and danger that would surround me; and that if I attempted to secure myself by fleeing from my habitation, and acted contrary to these intimations, which I believe to be Divine, it was a kind of flying from God, and that He could cause His justice to overtake me when and where He thought fit.

His brother, who wants him to leave, applies the same argument but concludes from it that he head for the country:

He told me the same thing which I argued for my staying, viz., that I would trust God with my safety and health, was the strongest repulse to my pretensions of losing my trade and my goods; ‘for’, says he, ‘is it not as reasonable that you should trust God with the chance or risk of losing your trade, as that you should stay in so eminent a point of danger, and trust Him with your life?’

H.F. stays and, in the end, gives up trying to figure out the divine meaning of the plague. For some reason, he has survived, and for that he thanks God. He never achieves the clarity that one finds in Sophocles and Virgil, however.

Writing 200 years later, Katherine Anne Porter doesn’t overtly reflect on the greater significance of the 1918 influenza that somehow spares the protagonist but not her lover in the autobiographical novella Pale Horse, Pale Rider (1939). The story, however, emphasizes the arbitrariness of the disease. With 20th century existentialism, we enter into the possibility that there is no transcendent meaning to cataclysm and that life is consequently absurd. This vision is at the heart of Camus’s La Peste (1947).

Yet Camus concedes that we cannot live without vision and concludes that, even if life is indeed meaningless, we still must proceed as though meaning exists. In his case, he finds this meaning in our common humanity, which somehow persists in spite of all that confronts us.

Stephen King comes to a similar conclusion in The Stand (1978). The survivors of a flu strain that has escaped the biological weapons lab divide into two groups, the good and the evil. By having the good guys win, King concludes, like Camus, that humans have more positive in them than negative.

Emily St. John Mandel grapples with existential “meaning of life” issues in Station Eleven (2014), where we watch a traveling group of actors and musicians attempt to find meaning in the face of an influenza that has wiped out most of the earth’s population. In their case, they turn to Art—to music, Shakespeare, and a mysterious, privately published graphic novel. They regard Art as an undefined higher need, critical because “survival is insufficient.” Humans need more than food, shelter, and safety, and in that need is something transcendent.

We see someone constructing higher meaning in Margaret Atwood’s Oryk and Crake. Jimmy is tasked with helping a new race develop a mythology following a pandemic engineered by his friend Crake. A brilliant genetic engineer, Crake plays God by exterminating humanity—most humans, anyway–and creating a new environmentally sensitive race to take their place. Jimmy tells the “Crakers” origin stories—how Crake created them, what his design was—and the stories come to give their lives direction and purpose. In this mythology, Crake’s girlfriend Oryk becomes a sustaining mother goddess.

I mention one other work, Louise Erdrich’s Tracks (1988), where devastating illness threatens to overwhelm the Anishinaabe Indians in 1912. In the account of village elder Nanapush, the tribe and their spirits, already under unrelenting assault by white culture, barely survive:

We started dying before the snow, and like the snow, we continued to fall. It was surprising there were so many of us left to die. For those who survived the spotted sicknss from the south, our long fight west to Nadouissioux land where we signed the treaty, and then a wind from the east, bringing exile in a storm of government papers, what descended from the north in 1912 seemed impossible.

…This disease was different from the pox and fever, for it came on slow. The outcome, however, was just as certain. Whole families of your relatives lay ill and helpless in its breath. On the reservation, where we were forced close together, the clans dwindled. Our tribe unraveled like a coarse rope, frayed at either end as the old and new among us were taken.

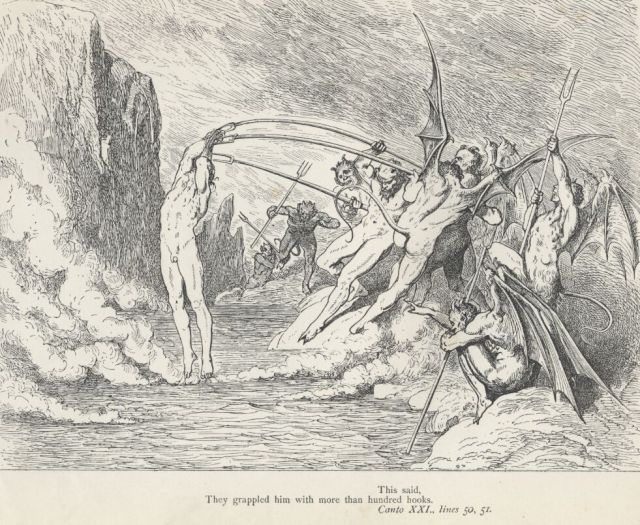

Later, Nanapush records mentions “windigo” as a secondary cause of death, windigo being an evil spirit who cannibalistically possesses human beings:

We had gone half windigo. I learned later that this was common, that there were many of our people who died in this manner, of the invisible sickness. There were those who could not swallow another bite of food because the names of their dead anchored their tongues.

And yet Nanapush and his adopted daughter Fleur, bolstered by their tribe’s protective spirits, keep fighting for survival and never entirely succumb. As in Porter, Camus, and Mandel, we watch in awe at how humans rise to the occasion in even the direst of circumstances.

Whether or not you believe in Zeus, Jupiter, God, the Anishinaabe lake spirit Misshepeshu, or the secular human spirit, they unleash survival powers within humans that can surprise us. There is more in heaven and on earth than is dreamt of in our everyday philosophy, and we can draw strength and courage from that knowledge as we struggle with our current pandemic.