Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Monday

Atlantic writer Tom Nichols, once a responsible Republican before Donald Trump drove him out of the party, has wondered whether the United States can be considered a serious nation. After all, why would we deliberately break institutions that are the envy of the world, including those tasked with curing disease.

Deliberate breakage seems to be Trump’s playbook in this area. Why else nominate for Health and Human Services Secretary the notorious anti-vaxxer Robert R. Kennedy, Jr., who is directly responsible for the measles deaths of 83 Samoan children? Why else nominate to head the National Institute of Health Dr. Jay Battacharya, whose proposal to allow Covid to spread in order to develop herd immunity would have resulted in another million deaths. (Instead we opted for masks and social distancing and were rewarded with the miraculous Covid vaccine.) Why else choose, as the top insurance regulator, Dr. Mehmet Oz, who has a history of hawking fraudulent medicines.

It appers that Trump aims to make infectious diseases great again.

In few areas has science proved its worth more than in battling illnesses that once claimed a horrific human toll. Following up on Tom Nichols’s observation, I have likened anti-vaxxers and their ilk to children born into wealthy families who take for granted their comfortable lives. Not having to be concerned about smallpox and polio and tuberculosis and cholera and typhus and typhoid and measles and whooping cough and chickenpox and a host of other diseases, they feel free to rail against the measures that have made their comfort possible.

Would they change their minds if they read the many 19th century novels that feature children dying of diseases that science has since found cures for? I like to think that the following heart-rending passages might make a difference.

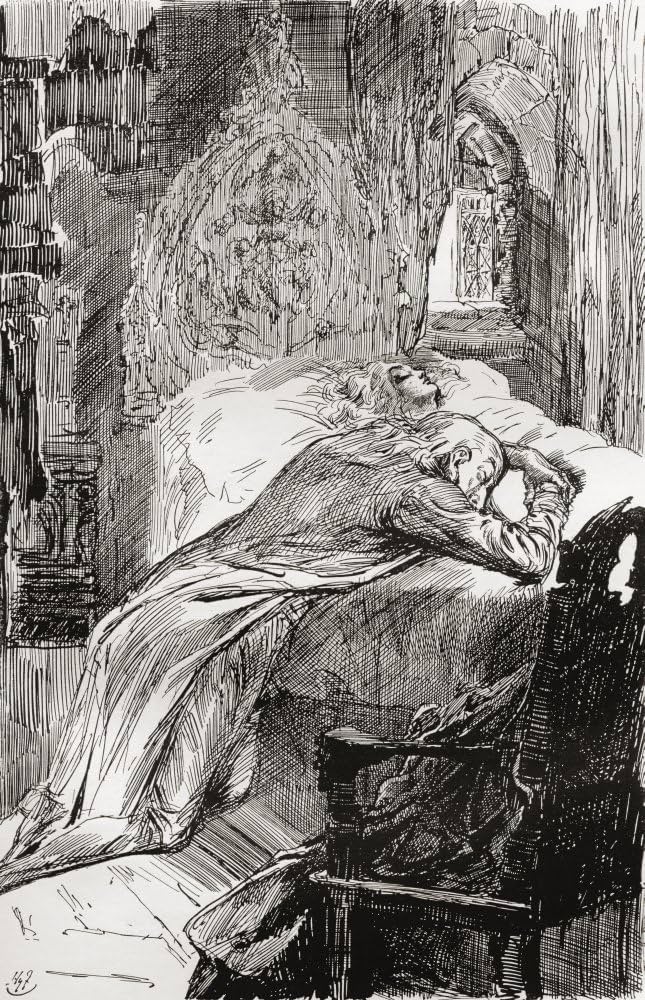

Little Nell in Charles Dickens’ The Old Curiosity Shop – Tuberculosis

“I have no relative or friend but her—I never had—I never will have. She is all in all to me. It is too late to part us now.’

Waving them off with his hand, and calling softly to her as he went, he stole into the room. They who were left behind, drew close together, and after a few whispered words—not unbroken by emotion, or easily uttered—followed him. They moved so gently, that their footsteps made no noise; but there were sobs from among the group, and sounds of grief and mourning.

For she was dead. There, upon her little bed, she lay at rest. The solemn stillness was no marvel now.

Little Jo in Dickens’ Bleak House – Smallpox

“It’s turned wery dark, sir. Is there any light a-comin?”

“It is coming fast, Jo.”

Fast. The cart is shaken all to pieces, and the rugged road is very near its end.

“Jo, my poor fellow!”

“I hear you, sir, in the dark, but I’m a-gropin—a-gropin—let me catch hold of your hand.”

“Jo, can you say what I say?”

“I’ll say anythink as you say, sir, for I knows it’s good.”

“Our Father.”

“Our Father! Yes, that’s wery good, sir.”

“Which art in heaven.”

“Art in heaven—is the light a-comin, sir?”

“It is close at hand. Hallowed be thy name!”

“Hallowed be—thy—”

The light is come upon the dark benighted way. Dead!

Carol in Kate Wiggins’ The Birds’ Christmas Carol – Tuberculosis

There were tears in many eyes, but not in Carol’s. The loving heart had quietly ceased to beat and the “wee birdie” in the great house had flown to its “home nest.” Carol had fallen asleep! But as to the song, I think perhaps, I cannot say, she heard it after all!

Tiny Tim in Dickens’ Christmas Carol – Possibly rickets, polio, cerebral palsy, or tuberculosis

The Ghost [of Christmas Future] conducted him through several streets familiar to his feet; and as they went along, Scrooge looked here and there to find himself, but nowhere was he to be seen. They entered poor Bob Cratchit’s house; the dwelling he had visited before; and found the mother and the children seated round the fire.

Quiet. Very quiet. The noisy little Cratchits were as still as statues in one corner, and sat looking up at Peter, who had a book before him. The mother and her daughters were engaged in sewing. But surely they were very quiet!

“ ‘And He took a child, and set him in the midst of them.’ ”

Helen Burns in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre – Tuberculosis, although the school itself is experiencing a typhus epidemic

“How comfortable I am! That last fit of coughing has tired me a little; I feel as if I could sleep: but don’t leave me, Jane; I like to have you near me.”

“I’ll stay with you, dear Helen: no one shall take me away.”

“Are you warm, darling?”

“Yes.”

“Good-night, Jane.”

“Good-night, Helen.”

She kissed me, and I her, and we both soon slumbered.

When I awoke it was day: an unusual movement roused me; I looked up; I was in somebody’s arms; the nurse held me; she was carrying me through the passage back to the dormitory. I was not reprimanded for leaving my bed; people had something else to think about; no explanation was afforded then to my many questions; but a day or two afterwards I learned that Miss Temple, on returning to her own room at dawn, had found me laid in the little crib; my face against Helen Burns’s shoulder, my arms round her neck. I was asleep, and Helen was—dead.

The parents in Francis Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden, leaving Mary an orphan – Cholera

The Mem Sahib wrung her hands.

“Oh, I know I ought!” she cried. “I only stayed to go to that silly dinner party. What a fool I was!”

At that very moment such a loud sound of wailing broke out from the servants’ quarters that she clutched the young man’s arm, and Mary stood shivering from head to foot. The wailing grew wilder and wilder. “What is it? What is it?” Mrs. Lennox gasped.

“Someone has died,” answered the boy officer. “You did not say it had broken out among your servants.”

“I did not know!” the Mem Sahib cried. “Come with me! Come with me!” and she turned and ran into the house.

After that appalling things happened, and the mysteriousness of the morning was explained to Mary. The cholera had broken out in its most fatal form and people were dying like flies. The Ayah had been taken ill in the night, and it was because she had just died that the servants had wailed in the huts. Before the next day three other servants were dead and others had run away in terror. There was panic on every side, and dying people in all the bungalows.

These 19th century authors, faced with child death, railed against those who could have made a difference. Here’s Bronte:

When the typhus fever had fulfilled its mission of devastation at Lowood, it gradually disappeared from thence; but not till its virulence and the number of its victims had drawn public attention on the school. Inquiry was made into the origin of the scourge, and by degrees various facts came out which excited public indignation in a high degree. The unhealthy nature of the site; the quantity and quality of the children’s food; the brackish, fetid water used in its preparation; the pupils’ wretched clothing and accommodations—all these things were discovered, and the discovery produced a result mortifying to Mr. Brocklehurst, but beneficial to the institution.

And Dickens in Bleak House after Jo has died of smallpox:

Dead, your Majesty. Dead, my lords and gentlemen. Dead, right reverends and wrong reverends of every order. Dead, men and women, born with heavenly compassion in your hearts. And dying thus around us every day.

Do we want to return to those days? Or would we like this instead?

Scrooge was better than his word. He did it all, and infinitely more; and to Tiny Tim, who did not die, he was a second father.

Which America is going to win out, Bad Scrooge or Good Scrooge? Tiny Tim’s life hangs in the balance.

Added nbote: Apparently there are further problematic health nominees that I missed when I wrote this essay. Thanks to David Corn of Mother Jones, I’ve learned to the following succinct tweet from Dr. Jonathan Reiner, professor of medicine, surgery interventional cardiologist, and CNN medical analyst. Corn added the names in brackets:

If a new pandemic comes to the US next year we’ll have an NIH director [Jay Bhattacharya] who advocated for letting COVID burn through the US, an HHS Sec [Robert F. Kennedy Jr.] who believes in raw milk but not vaccines, an FDA commissioner [Marty Makary] who said COVID would be over by 4/2021, and a CDC director [Dave Weldon] who supported the debunked theory that vaccines cause autism.