Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Friday

My friend and colleague Jennifer Michael, English professor, former Rhodes scholar, and wonderful poet, has a great short essay on how William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience and Stephen Sondheim’s Into the Woods share a similar view of children. While adults may obsess about childhood innocence, Blake and Sondheim point out that they can fail to hear how hungry their kids are for experiences that will help them grow. In fact, both authors show how parents who claim to be protecting their children are often more interested in controlling and molding them.

While Jennifer’s article doesn’t take on the current MAGA obsession with banning books and dictating school curricula, one certainly sees this dynamic at work in politicians such as Ron DeSantis and organizations like Moms for Liberty.

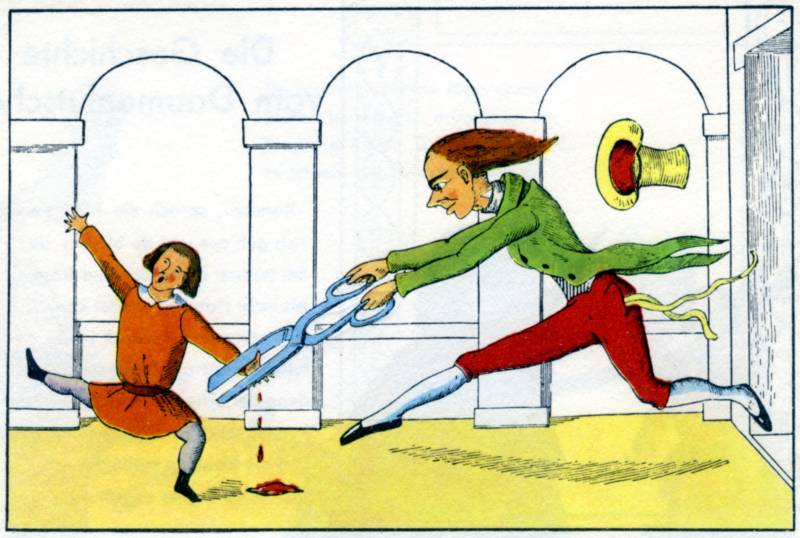

Jennifer wrote her article after witnessing a high school production of Into the Woods. There she noticed that the wolf ushers little Red Riding Hood into the world of experience, his predation being

as much sexual as carnivorous. While we don’t see exactly what happens between them, we hear about it in Red’s account later: “He showed me things that I never had seen.” Experience brings wonder.

This in turn got her thinking of Blake, “who saw desire as part of innocence, not as a corruption of it.” Like Sondheim, , she says, Blake

uncovered the darker elements of children’s literature, exploring the interplay of innocence and experience, desire and repression. Both writers see the loss of innocence as not an end but a beginning—a fortunate fall.

Jennifer notes that Sondheim’s characters must journey into the woods “to achieve and examine their desires.” Because the woods are “suffused with mystery and danger,” they operate as a psychological symbol of the unconscious. (Other literary examples of this include Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, The Scarlet Letter, and Deliverance.) Red, therefore, must venture into these woods if she is to grow up, just as Jack must climb his beanstalk. Jennifer cites Joseph Campbell in noting that, in the archetypal journey, “regardless of what material object is found, the real prize is knowledge.” Or as Jack puts it, “You know things now that you never knew before.”

Sondheim, Jennifer says, makes a distinction between “nice” and “good,” nice applying to Cinderella’s Prince Charming (“wanting a ball is not wanting a prince,” she discovers), “good” applying to Red’s wolf. The prince doesn’t do Cinderella any good when she marries him whereas Red is profoundly altered for the better when she emerges from the wolf’s belly.

Let’s turn now to Blake, where the same distinction applies. To be sure, it’s a little confusing since the word “good” is often used as a synonym for “nice.” When parents want children to “be good,” they often mean well behaved:

Like Rousseau, Blake asserted that children’s impulses were naturally good, but the admonishment to “be good” often means to squelch those impulses in the name of conformity. (As Cinderella asks in the show’s opening number, “What’s the good of being good if everyone is blind?”)

For Blake, squelching is always bad. What looks like nice innocence can actually be a “polite superficiality” that poisons our feelings, as in “A Poison Tree”:

I was angry with my friend;

I told my wrath, my wrath did end.

I was angry with my foe:

I told it not, my wrath did grow.

Jennifer points out that the poison plant is fed by the speaker’s “false smiles and crocodile tears.” The final effect is deadly:

And I waterd it in fears,

Night & morning with my tears:

And I sunned it with smiles,

And with soft deceitful wiles.

And it grew both day and night.

Till it bore an apple bright.

And my foe beheld it shine,

And he knew that it was mine.

And into my garden stole,

When the night had veild the pole;

In the morning glad I see;

My foe outstretched beneath the tree.

Throughout Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience one sees adults forcing niceness upon children without listening to their actual desires and needs. One thinks especially of how “grey-headed beadles” force-march orphans to church in “Holy Thursday” (in Innocence):

Twas on a Holy Thursday their innocent faces clean

The children walking two & two in red & blue & green

Grey-headed beadles walkd before with wands as white as snow,

Till into the high dome of Pauls they like Thames waters flow

If your response to these lines is, “Isn’t that sweet?” you’ve missed Blake’s sarcasm. (It’s subtle but fueled by an immense rage.) One could also cite here Blake’s provocative proverb from “Marriage of Heaven and Hell,” “The tygers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction.” (Note: to get a sense of the stifling instruction ladled out to 19th century children, check out my recent post on Lewis Carroll and Hilaire Belloc, who satirized it.)

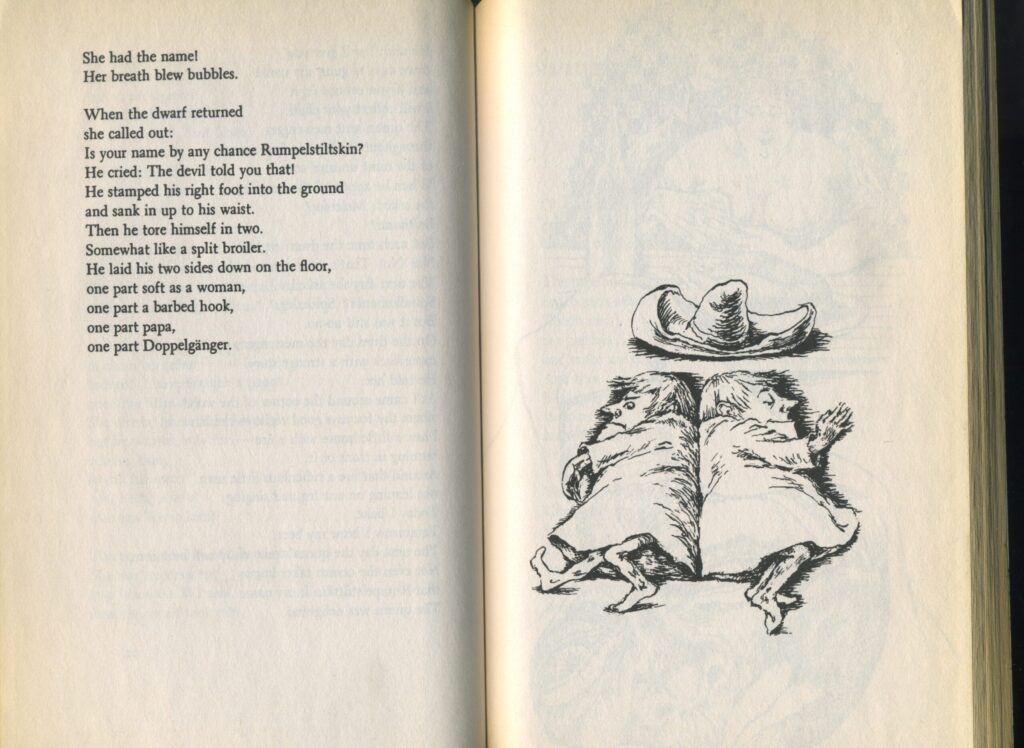

Far healthier are the parents in “The Little Girl Lost” and “The Little Girl Found,” which Jennifer says Blake moved from Songs of Innocence to Songs of Experience. In the poems Lyca

goes missing in the “desert wild.” Her parents find her among lions and tigers, not injured but (we assume) sexually awakened. Rather than respond with fear and outrage, however, they join her there:

To this day they dwell

In a lonely dell,

Nor fear the wolvish howl,

Nor the lions’ growl.

Jennifer also approves of the Nurse in “Nurse’s Song” (in Innocence), where the Nurse “accedes to the children’s desire to stay out until it is dark”:

Well well go & play till the light fades away

And then go home to bed

The little ones leaped & shouted & laugh’d

And all the hills echoed[.]

[Side note: When Allen Ginsberg came to our college, he spent at least thirty minutes having us all sing the poem—especially the last line—to the accompaniment of a small harmonium. The effect was hypnotic and memorable.]

Jennifer observes that both Blake and Sondheim “recognize the power of stories, especially in the imaginations of children.” Narratives, she points out, “can be far more seductive and persuasive than instructions.” And she concludes,

Into the Woods follows Blake in encouraging its audience to question the tales we are told and the tales we tell, particularly their beginnings and endings. There is always something that happens before “once upon a time,” and something that follows “happily ever after.” In “The Tyger,” Blake’s speaker asks who can “frame [the] fearful symmetry” of human nature—one answer is the theater. The great genius of Into the Woods is that it allows us to be at once inside and outside that frame, to give ourselves, for a time, to the “forests of the night,” and return home braver and wiser.

All those who want to keep children from reading “dangerous books” are like Blake’s “grey-headed beadles.” As I say, they are not interested in growth but in control. If they have their way, Red, Jack, and all those others will never venture into the woods at all but will grow up dull and resentful, trapped in the confines of a narrow ideology.