Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Wednesday

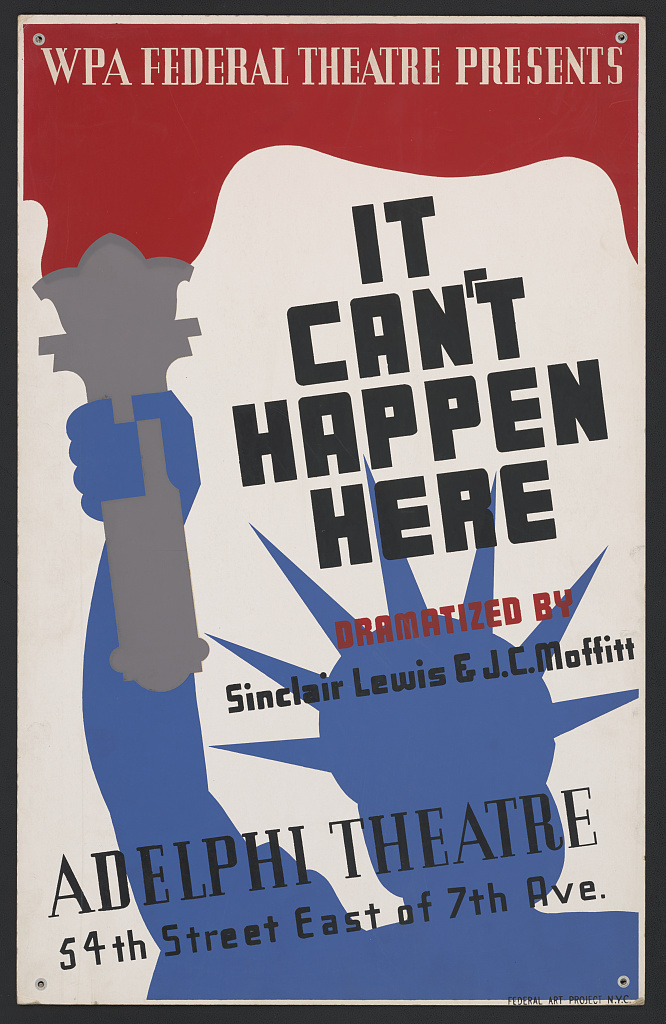

David Corn of Mother Jones has announced a new series of short videos on the very real danger of a fascist takeover of the United States. In a reference to Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 novel It Can’t Happen Here, Corn has entitled the series It Can Happen Here.

Of course, Lewis too believed that it could happen here, with his title designed to jolt American moderates, liberals and leftists out of any complacency. As Corn explains in the blog post announcing the series, Lewis’s novel

was a reaction to the rise of Hitler and Mussolini in Europe and the spread of demagogic populism in the United States by Huey Long, the strongman governor of Louisiana, and Father Charles Coughlin, the wildly popular antisemitic radio preacher. In Lewis’ alternative universe, a politician named Buzz Windrip, who champions “traditional” values and who promises to restore America to greatness, defeats FDR in the presidential election of 1936 and then through a self-coup seizes dictatorial powers. He establishes a paramilitary force to do his bidding, curtails the rights of women and minorities, and locks up dissidents and political foes in concentration camps. Eventually, his reign leads to civil war. It’s a grim tale.

If 1930s America did not succumb to the fascist wave, Corn says, it was in part due to the assassination of Long, to Coughlin being forced off the air, and to Pearl Harbor and the United States’ entry into World War II. So no Buzz Windrip emerged.

But we have a Buzz Windrip now as MAGA fascists pray that Trump will make their fever dreams come true. We saw their desires in full living color at last week’s gathering of the Conservative Political Action Conference, during which time (according to Corn)

top strategist of the MAGA right, Jack Posobiec, a prominent conspiracy theorist of the alt-right, declared, “Welcome to the end of democracy. We are here to overthrow it completely. We didn’t get all the way there on January 6, but we will endeavor to get rid of it and replace it with this right here.” He apparently was referring to the Trumpian vanguard present in the room, and [Trump supporter Steve] Bannon interjected, “Amen.” Posobiec, an early promoter of the Pizzagate conspiracy theory that led to a dangerous shooting at a Washington, DC, restaurant, added, “All glory is not to government. All glory to God.”

Other declarations at CPAC included Gov. Kristi Noem of South Dakota proclaiming, “There are two kinds of people in this country right now. There are people who love America, and there are those who hate America,” and Trump adviser Stephene Moore asserting that “one of the most evil left-wing organizations in America is the AARP” (!). Shifting novels, Corn notes that “Trump and his minions were engaged in an orgy of despisal akin to the ‘Two Minutes of Hate’ Orwell imagined in 1984.” If you need a reminder, here’s Orwell’s account:

The horrible thing about the Two Minutes Hate was not that one was obliged to act a part, but, on the contrary, that it was impossible to avoid joining in. Within thirty seconds any pretense was always unnecessary. A hideous ecstasy of fear and vindictiveness, a desire to kill, to torture, to smash faces in with a sledgehammer, seemed to flow through the whole group of people like an electric current, turning one even against one’s will into a grimacing, screaming lunatic…. At those moments his secret loathing of Big Brother changed into adoration, and Big Brother seemed to tower up, an invincible, fearless protector, standing like a rock against the hordes of Asia, and Goldstein, in spite of his isolation, his helplessness, and the doubt that hung about his very existence, seemed like some sinister enchanter, capable by the mere power of his voice of wrecking the structure of civilization.

So how worried should we be when Trump labels his political foes as “vermin” or accuses migrants of “poisoning the blood” of the United States? Would a reelected Trump go as far as Windrip? Corn points out that he

vows to deport millions of people, which would require massive detention camps. He has consistently pledged he would prosecute and imprison his critics and rivals. He has said (jokingly or not) he would act as a dictator only on his first day in office. He has threatened to use the power of government to crush media outlets he doesn’t favor. This is all Windripish. Moreover, throughout MAGA-land, it’s easy to find Trumpists who denigrate democracy and scheme workarounds to direct elections. And the Alabama Supreme Court justice who last week handed down an opinion stating that fertilized embryos are people—a ruling that imperils in vitro fertilization treatments—has stated that the Bible dictates that conservative Christians ought to rule over government, as well as business, media, and education.

Someone, perhaps Lewis, once remarked that when Fascism comes to America, “it will be wrapped in the flag and carrying a cross.” In what can serve as a response, someone else said (perhaps Thomas Jefferson but again we don’t know for certain), “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.” Dystopian novels like It Can’t Happen Here, 1984, and, more recently, Philip Roth’s The Plot against America (2004) are designed to keep us vigilant. Liberty is too precious a gift to squander.