Wednesday

In recent weeks, I’ve read several articles on rereading, all connected in one way or another with the current pandemic. Two of them discuss how rereading comforts us while the third counters that the purpose of narrative is not to reassure us.

The New York Review of Books, probably with the pandemic in mind, recently reprinted a 2005 Larry McMurtry article on why he rereads. “Reversal of fortune,” he says, “can…be a spur to rereading; where once one had read for adventure, now one rereads for the safety of the unvarying text.”

McMurtry mentions the example of Virginia Woolf’s mother-in-law, who reread Samuel Johnson’s Rasselas “dozens of times” after her husband died. As McMurtry explains,

Marie Woolf didn’t expect her husband Sidney to die at age forty-seven, but one day in 1892 Sidney Woolf did just that. The much-respected Mr. Floyd, tutor to the young Woolfs and himself a Rasselas fan—he kept a copy in his pocket—probably suggested the book to Marie Woolf. Rasselas cannot have entirely consoled her for the loss of a husband, and yet it was something. The husband was gone, the book remained, a small comforting thing whose absolute sameness could be counted on.

I can see why Rasselas, which explores the elusiveness of human happiness, would speak to someone who has just lost her husband. It stimulates an active mind while offering up no easy answers (or any definitive answers whatsoever).

McMurtry then talks about what rereading has done for him:

I’ve spoken elsewhere of the effects of heart surgery on my own reading: the knife that takes away the flaw can also remove, for a time at least, the personality of the flawed. After that surgery, my name seemed to me to be no more than a loose rubric under which, at intervals, aspects of myself occasionally reassembled and functioned.

It was about that time that I too, like Marie Woolf, began to reread in my search for security. At first I reread a few great travel books—there are only a few great travel books. Rebecca West’s Black Lamb and Grey Falcon is one and Wilfred Thesiger’s Arabian Sands is another….Survival means adjustment, and, if reading has for a long time been the central activity of one’s life, as it has of mine, then a shift in the patterns of reading and rereading is no small thing.

I assume that, by shift in patterns, McMurtry means becoming more exploratory in his reading, something he chooses not to do at such moments.

Natalie Jenner for Literary Hub doesn’t mention the pandemic, but it may account for her writing her article at this time. Jenner is drawn to old favorites because of their familiarity:

First for me is voice. Certain authorial voices calm me down, like a child listening to its parent. Whenever I read Jane Austen or Edith Wharton, something about their syntax soothes me in the same way the measured, marching tone of a cantata by Bach does. Austen and Wharton’s matchless gifts for prose has run deep grooves into my brain upon every reread, and each time I open their books I get more satisfaction with less effort, until it feels like their voices and my own have merged. Lines like Wharton’s “they all lived in a kind of hieroglyphic world” or Austen’s “I am half agony, half hope” are as much music to me as anything I have ever heard.

As with McMurtry, Jenner rereads to reassure herself that things haven’t entirely changed:

[U]ltimately, I’d like to think we reread in order to recover a sense of the distance traveled between our younger and present selves, and how—despite the passage of time—we can be just as thrilled, moved, and satisfied by the very same things now as then. I rely on all my old favorites as touchstones for my own essential self—every time Father Ralph leaves Meggie Cleary on Matlock Island in The Thorn Birds, or Mr. Rochester finally comes clean with Jane Eyre and says he feels as if there is a little string running straight from his heart to hers, I feel the same romantic thrill that I did when I was 14, and I “own” the romanticism that has been my own folly, and guide, throughout my life.

David L. Ulin appears to react against reading for familiarity. In the early days of the pandemic, he writes, he wanted a “guide for living.” He therefore turned to practical non-fiction because he resists “the notion that literature should have to teach us anything, that it must necessarily be of use.”

Needless to say, this sentiment is at odds with my blog, which relentlessly insists that literature can be of use. Indeed, Ulin circles back to Faulkner before he’s done. But I understand why he would turn to practical essays first:

What I wanted were tips on how to make it through. What I wanted were assurances, a sense that everything was going to be OK. This, however, is not the purpose of narrative, which insists on a more rigorous perspective. We don’t read or write to be reassured — at least I don’t. We read and write to reckon with all the things we cannot know.

Ulin objects to “sentimental” rereading because he regards it as a desire to return to a normalcy that may never return. “The more you remember,” he quotes from Emily St. Mandel’s post-pandemic novel Station Eleven, “the more you’ve lost.” He, by contrast, rereads for insights he missed when circumstances were different:

I’ve carved a passage back to reading by discovering new reflections on life under the duress of quarantine or illness, while also revisiting older works that affirm for me a related point, which should be obvious — that nothing is unprecedented, even if it feels that way. What I mean is, disorder and plague are always with us. “[W]e’re all just a breath away from the end of our lives,” Jenny Diski wrote in her 2016 memoir, “In Gratitude,” one of the books I’ve been rereading.”

So literature becomes of use after all, addressing the isolation he is feeling. For all his protesting against reassurance, he is reading to reassure himself that he is part of a greater collectivity:

All the same, stories are (How can they not be?) connective, part of a collective narrative. That seems especially essential now that we find ourselves in isolation, not only physically but also emotionally. I remember how, as an adolescent, the books I read, and the people I met there, felt as real to me (or realer) than those with whom I dealt every day. Escape? Perhaps, but I prefer to think of it as a deeper engagement, a conversation across space and time. We are alone, yes, but there is togetherness — if only in the fact that we are all laboring under the same condition, which is the frailty and uncertainty of being human.

I particularly like what he says about Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying:

Not long ago, via email — or was it Zoom or Skype? — a friend commented that she missed Los Angeles. “I miss it too,” I responded, looking at the street outside my window, where I have lived for the last 15 years. There it was, on the other side of the glass, like a scene from a life that no longer belonged to me. It brought to mind Addie Bundren, the dying matriarch who catalyzes William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, “quilt … drawn up to her chin, hot as it is, with only her two hands and her face outside,” watching through her own window as her son Cash builds the coffin in which she will be committed to the void.

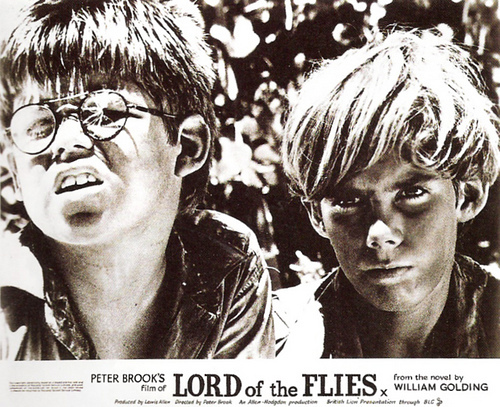

As I Lay Dying is another work to which I keep returning, not because it offers easy solace but because it does not. Faulkner makes that clear from his first description of Addie: “Her eyes are like two candles when you watch them gutter down into the sockets of iron candle-sticks. But the eternal and the everlasting salvation and grace is not upon her.”

The portrait is astonishing; even as she faces the inevitable, she is not willing to let go. The insight here? Acceptance of death is what we need, not preparation for it. It brings to mind a similar moment toward the end of “In Gratitude,” in which Diski listens as another patient wails in terror. “[S]he’s not ready,” a nurse explains. “She hasn’t thought enough about it and now it’s very hard for her.” The inference is that there’s work to be done, some preparation to ease our passage. But the truer lesson may be that readiness is immaterial, that acceptance is what we require. To imagine otherwise is a sentimental fantasy, which is a luxury we cannot (Could we ever?) afford.

By the end of the essay, Ulin concludes he treasures how older works help us persevere and become resilient. In tough times, he writes, we are reminded that this is literature’s most defining aspect. We think we are in uncharted territory and then discover that the great authors have already been there and charted it:

“How often,” Faulkner writes, “have I lain beneath rain on a strange roof, thinking of home.” It’s an open-ended question, but in its specificity — rain on a strange roof? — it offers something sustaining: a sense of what it means to live each moment on its own terms, and a reminder that in a time that feels unmapped and raw, we have been here before.

We can say of great literature what German philosopher and culture critic Walter Benjamin says of history. In his essay “On the Concept of History,” he writes that the past “can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized” and that we “seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.”

In other words, we see in the past what we need for the present. When we are experiencing moments of danger, works will flash up.

If we have read them, that is. This is an argument for reading extensively. We are storing up supplies, even though we don’t know how or when we will use them.