Wednesday

As I continue to work my way through Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series, I’ve come across one that imaginatively addresses factional and police violence. Even more impressively, it shows how most of us have a dark side, which will rob us of our souls if we surrender to it.

In Thud!, age-old tensions between dwarfs and trolls threaten to erupt on the anniversary of the Battle of Koom Valley, a famous conflict that occurred 500 years earlier. Pratchett may be thinking of the 1389 Battle of Kosovo, in which Christian Serbs battled with Ottoman Turks and which was invoked frequently to justify the Bosnian civil war. Since the novel was written in 2005, Pratchett probably also has in mind various Muslim terrorist organizations, although I won’t rule out anti-immigrant hatred in Britain or white supremacy in America. At any rate, Inspector Samuel Vimes, head of the Night Watch, is attempting to maintain the peace.

To do so, he has assembled a diverse police force consisting of humans, dwarfs, trolls, werewolves, zombies, golems, wee men, and (reluctantly on his part given his prejudices) vampires. He even insists on sending out troll and dwarf officers together, which would be comparable to pairing up, say, Italian and Irish officers in late 19th century Boston. At the end, Vimes makes a discovery that establishes a new peace between dwarfs and trolls.

The battle of Koom Valley, counter to dwarf and troll accounts, actually ended indecisively as a flash flood swept away both sides. Some of these were entombed together and, before they died, they arrived at a truce and left behind both voice and sculpted records of their new understanding. These records, having resurfaced, are now the target of fanatical dwarfs, just as Afghanistan’s great Buddhist statues were blown up by the Taliban in 2001. Like ISIS members, these dwarfs also kill those fellow dwarfs who stumble across the ancient account of the truce. In the novel’s happy ending, the truth emerges anyway and the caverns that served as a tomb for trolls and dwarfs becomes a shrine.

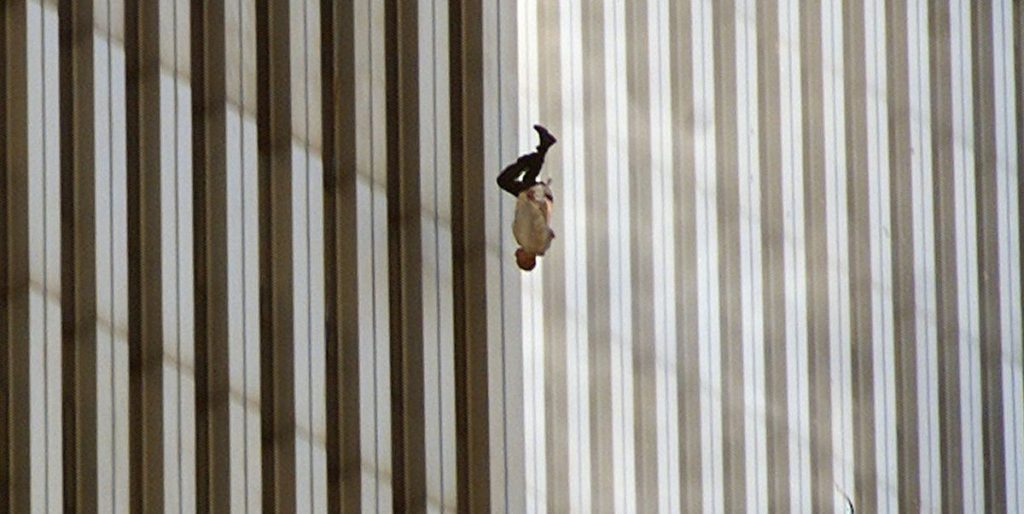

There’s another plot element that makes Thud! particularly relevant given police violence. A primal hatred called the Summoning Darkness is looking for a way to gain entry into the world, and its chosen vehicle is Inspector Vimes himself. When fanatical dwarfs attack his home and threaten his wife and child, he is prepared to enact extra-judicial violence against, not just these dwarfs, but dwarfs in general. At moments, he is desperately hoping that dwarfs will take a punch at him so that that he can unload his fury. He is prepared to lash out at the local dwarf businessmen who show up at the precinct station, just as some Americans wanted to lash out at all Muslims following 9-11. Here’s his interior monologue:

You scum you rat-sucking little worm-eaters! You heads-down little scurries in the dark! What did you bring to my city? What were you thinking? Did you want the deep-downers [the extremist dwarfs] here? Did you dare deplore what Hamcrusher said, all that bile and ancient lies? Or did you say, “Well, I don’t agree with him, of course, but he’s got a point”? Did you say, “Oh, he goes too far, but it’s about time somebody said it”? And now have you come here to wring your hands and say how dreadful, it was nothing to do with you? Who were the dwarfs in the mobs, then? Aren’t you community leaders? Were you leading them? And why are you here now, you ugly, sniveling grubbers? Is it possible, is it possible, that now, after that bastard’s bodyguards tried to kill my family, you’re here to complain? Have I broken some code, trodden on some ancient toe? To hell with it. To hell with you.

Although these dwarfs have only shown up to help—in fact, some of themselves lost family members to the deep downers—Vimes has trouble seeing it. I could well imagine Pratchett channeling some of his own prejudice at this moment, both voicing it and realizing how dangerous it is. Fortunately, he arrives at some self awareness when he is dealing with a deep-downer in custody:

And he was not certain, not certain at all, what he’d do if the prisoner gave him any lip or tried to be smart. Beating people up in little rooms…he knew where that led. And if you did it for a good reason, you’d do it for a bad one. You couldn’t say “we’re the good guys” and do bad-guy things. Sometimes the watching watchman inside every good copper’s head could use an extra pair of eyes.

Vimes is not the only character in danger of being swallowed by darkness. Two of his officers, a werewolf and a vampire, have their own issues. The vampire, who has taken the pledge and belongs to the Black Ribbon society (akin to AA), has learned to settle for biting beetroots or, when nothing is available, apples. The werewolf, meanwhile, has learned to control her transformations and curb her wolfish impulses. The novel’s central drama, however, is Vimes’s own interior battle.

Parents will appreciate how he holds on to his humanity: he reads to his two-year-old son every night at six. The book he reads sounds like a take-off of P.D. Eastman’s Are You My Mother, only it is based on the question, “Where’s my cow?” Patchett’s description is hilarious. Following various false leads involving a sheep and a horse (“Is that my cow? It goes naaaay! It is a horse!”) the book reaches its crescendo:

At this point, the author had reached an agony of creation and was writing from the racked depths of their soul.

Where’s my cow?

Is that my cow?

It goes HRUUUUGH!

It is a hippopotamus!

No, that’s not my cow!

This was a good evening. Young Sam was already grinning widely and crowing along with the plot.

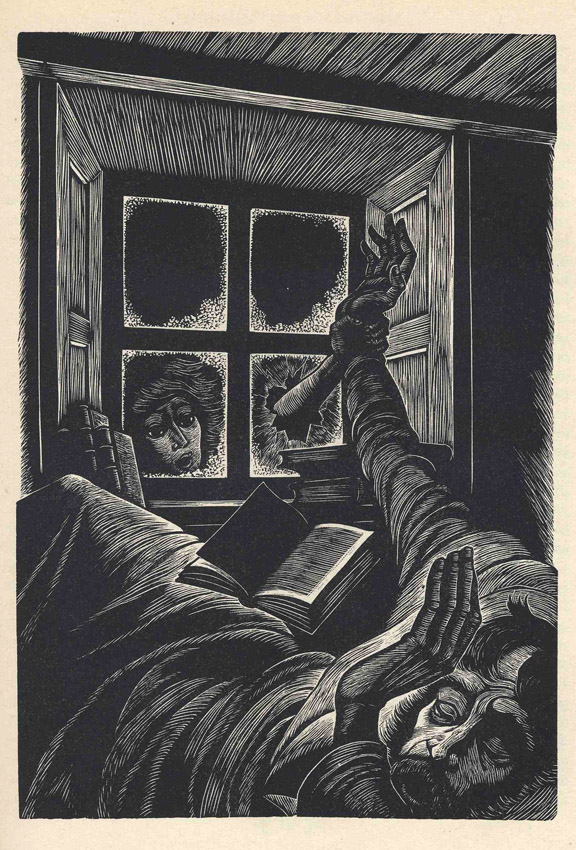

In Thud!’s own climactic moment, Vimes confronts the dwarfs who attacked his home in an underground cavern that is metaphorically his interior self. The Summoning Darkness thinks it has found a way into the world through him, only to learn that the watchman can indeed watch himself:

“I am the Summoning Dark.” It was not, in fact, a sound, but had it been, it would have been a hiss. “Who are you?”

“I am the Watchman.”

“They would have killed his family!” The darkness lunged, and met resistance. “Think of the deaths they have caused! Who are you to stop me?”

“He created me. Quis custodiet Ipsos custodes? What watches the watchman? Me. I watch him. Always. You will not force him to murder for you.”

“What kind of human creates his own policeman?”

“One who fears the dark.”

“And so he should,” said the entity, with satisfaction.

“Indeed. But I think you misunderstand. I am not here to keep darkness out. I’m here to keep it in.” There was a clink of metal as the shadowy watchman lifted a dark lantern and opened its little door. Orange light cut through the blackness. “Call me…the Guarding Dark. Imagine how strong I must be.”

The Summoning Dark backed desperately into the alley, but the light followed it, burning it.

“And now,” said the watchman, “get out of town.”

One of the conciliatory dwarfs later reveals worries that Vimes’s struggle with the Summoning Dark “would rip your tendons from your bones.” By channeling “That’s Not My Cow,” however, the inspector reveals his interior strength.

Americans live in a country where the chief executive is trying to summon the Darkness. He did this when he suggested to an assembly of police not to be “too nice” to the suspects they arrested. He wants his military to kill the families of terrorists, he advocates tearing children away from their refugee parents, and he defends (on the grounds of self-defense) the armed vigilante who killed two protesters in Kenosha, Wisconsin. His violent dreams have led to an upsurge in rightwing violence over the past four years.

It’s up to America to resist the Summoning Darkness. Terry Pratchett’s comic fantasy shows us how.