Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Wednesday

My friend Sue Schmidt recently alerted me to an enlightening article about “What Shakespeare Can Teach Us about Racism.” I’ve argued “a lot” in past essays on Othello, Merchant of Venice, and The Tempest, but Professor David Stirling Brown has opened my eyes to further dimensions.

Brown says that scholars view these three plays plus Titus Andronicus and Antony and Cleopatra as Shakespeare’s five “race plays,” and his naming Titus Andronicus as his favorite play was the spur I needed to go read it. (It’s one of the few I hadn’t read, the others being Two Gentlemen of Verona, Pericles, Henry VIII, King John, and Timon of Athens.)

My response to Titus was, “Oh my God!” One of Shakespeare’s earliest dramas (1591/92), it has as much casual sadism, as much blood and gore, as a Quentin Tarantino film. A Goth prisoner is executed as a sacrifice, Roman general Titus kills one of his sons for disobeying him, and then there’s the mayhem unleashed by Tamora, a captive Goth queen who becomes Roman empress when the emperor marries her. Because it is one of her sons that has been sacrificed, she goads her other two sons to attack Titus’s daughter Lavinia, along with Lavinia’s husband. (Following the rape, they rip out Lavinia’s tongue and cut off both hands so she can’t testify against them.) Then, with the help of her moor lover Aaron, Empress Tamora frames two of Titus’s sons for the husband’s death, leading to their execution.

Not, however, before Aaron has told Titus that, if he sacrifices his hand, the emperor will spare his sons. Titus, who has already lost 21 sons (!) in battling the Goths–not to mention the one he killed for disobedience–does so, and there’s even a sick Dad Joke when he asks for Aaron’s assistance: “Lend me thy hand, and I will give thee mine.”

Of course Aaron—an early forerunner of Iago as a character who unabashedly revels in being evil—has just been messing with him. Titus’s suit is rejected and his hand is returned to him, along with the heads of his two sons.

Shakespeare is just getting warmed up. Tamora, worried about Titus’s one remaining son—the exiled Lucius is off persuading the Goths to join him in a revenge conquest of Rome—seeks to use Titus to lure him into a trap. Titus, feigning madness, seems to play along and, in the process, gets her to leave her two sons with him (the ones who raped Lavinia and killed Lavinia’s husband). These he kills and uses their body parts as ingredients in a pie, which he then serves to Tamora and her emperor husband. Following this, there’s a final bloodletting in which she, the emperor and Titus all get stabbed. But not before Titus has killed his daughter Lavinia for having been dishonored. If you’re keeping count, 27 of his 28 children have been killed, two by himself.

And then there’s Aaron. His earlier relationship with the empress has resulted in a “coal-black” baby boy. Rather than kill the baby, he kills the midwives present at the birth (to hide the secret), substitutes a white child so that Tamora’s infidelity will remain a secret, and runs off with the child. He is captured by Lucius’s forces, to whom he reveals his perfidy, and is condemned to be starved to death while buried up to his neck in the ground. I guess one could say that the play ends happily since Lucius is named the new Roman emperor, but that’s just because Shakespeare always feels the need to restore political order at the end of his tragedies (think of Fortinbras, Edgar, and Malcolm).

Shakespeare being Shakespeare, there’s some good poetry in Titus Andronicus, including the chilling declaration by the two Goth boys about their intentions to “hunt” Lavinia during a hunting party: “Chiron, we hunt not, we, with horse nor hound,/ But hope to pluck a dainty doe to ground.” Still, the play lacks the deep psychology of a Hamlet or a King Lear. It’s Grand Guignol spectacle, not moving tragedy.

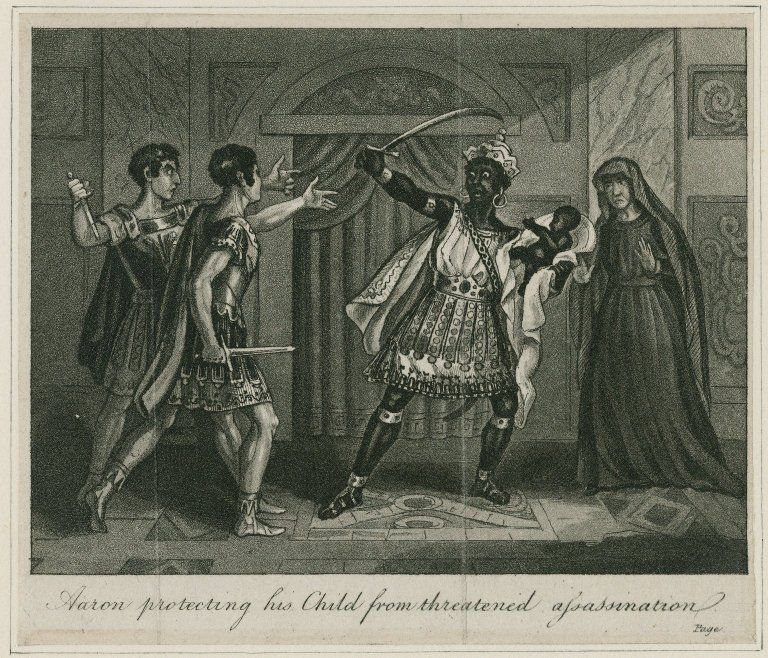

Except, perhaps, for the scene that draws Professor Brown to the play, which is in fact extraordinary. Tamora’s two sons want to kill the baby since its skin color will expose their mother, but Aaron, the baby’s father, holds them off. Brown notes that Shakespeare “momentarily offers a beautiful defense of Blackness”:

What, what, you sanguine, shallow-hearted boys,

You white-limed walls, you alehouse painted signs!

Coal-black is better than another hue

In that it scorns to bear another hue;

For all the water in the ocean

Can never turn the swan’s black legs to white,

Although she lave them hourly in the flood.

Tell the Empress from me, I am of age

To keep mine own, excuse it how she can.

Aaron, Brown points out, is challenging the cultural norm here, arguing that Black is beautiful and strong. The scholar adds that one finds such an endorsement of Black identity nowhere else in Shakespeare, even in Othello. (I would add that Othello not only fails to celebrate Blackness but that Othello’s defensiveness about his skin color makes him vulnerable to Iago’s manipulation.)

Brown contends that Shakespeare helps us understand race even in those plays where there are no characters of color. In these instances, the Bard examines whiteness, which wasn’t an automatic identity marker before the 17th century. In other words, Shakespeare was writing at a time when people were just beginning to define themselves by racial characteristics, with the elite (but not the working class) seeing themselves as white. As Brown notes, Shakespeare “details the nuances of race through his characters’ racial similarities, thus making racial whiteness very visible.”

Shakespeare, with his powerful poetry, does bear some responsibility for establishing race as a marker. Brown cites the collection of essays White People in Shakespeare, reviewed in The Atlantic (paywalled), which contends that “Shakespeare’s work … was central to the construction of whiteness as a racial category during the Renaissance.” In addition to that, white people “have used Shakespeare to regulate social hierarchies ever since.” The collection contends that “what’s beautiful in Shakespeare,—or what Shakespeare’s speakers take as beautiful—is often cast in racial terms.”

For instance, Brown says, in several of his plays Shakespeare uses white hands as “noble symbols of purity and white superiority.” He also will call attention to a character’s race by describing him/her as “white” or “fair.”

And then there’s the opposite, when black gets used as an insult: the fair Hero in Much Ado about Nothing, who has been falsely accused of an affair, is described by her father as having “fallen into a pit of ink.” Brown says that hero momentarily represents “an ‘inked’ white woman – or a symbolic reflection of the stereotyped, hypersexual Black woman.”

Shakespeare’s role in establishing whiteness as a virtue has proved problematic for some otherwise fervent admirers. Harold Bloom, Shakespeare’s #1 fan, believes that Shakespeare’s creation of Shylock did more damage to Jews than did the fabricated Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the infamous anti-Semitic text that played a key role in Nazi propaganda.

Sir Philip Sidney, in his Defense of Poetry, acknowledges that good things can be perverted to bad and that poetry is no exception. It is like a sword, he says, that can both heroically defend freedom and basely promote tyranny. That being noted, there are those who defend Shakespeare’s creation of Shylock, including leading Shakespeare scholar Stephen Greenblatt. Even while Shakespeare was giving us an unforgettable image of the moneylending Jew, Greenblatt writes, he was simultaneously exploding the stereotype. While we shy away in horror from Shylock’s demand for a pound of flesh, at the same time we see his full humanity, along with the ugliness of those who mock him. Brown appears to me making such a defense of the evil-but-fatherly moor in Titus Andronicus.

In his essay Brown argues for the openness of James Baldwin, who once condemned Shakespeare as “one of the authors and architects of my oppression” but later changed his mind. The Bard, Baldwin writes, “found his poetry where poetry is found: in the lives of the people.” Shakespeare, he adds, “could have done this only through love—by knowing, which is not the same thing as understanding, that whatever was happening to anyone was happening to him.”

Baldwin concludes that Shakespeare’s “responsibility, which is also his joy and his strength and his life, is to defeat all labels and complicate all battles by insisting on the human riddle, to bear witness, as long as breath is in him, to that almighty, unnameable, transfiguring force which lives in the soul of man.”

Or as Brown, less poetically, puts it,

Just as Shakespeare didn’t create misogyny and sexism, he didn’t create race and racism. Rather, he observed the complex realities of the world around him, and through his plays he articulated an underlying hope for a more just world.

Or to put it even more succinctly, Shakespeare understood people at a deeper level than anyone ever has.