Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Wednesday

The Atlantic’s Adam Serwer, writing about Trump policies separating migrant children from their parents and putting them in cages, once noted that “the cruelty is the point.” The observation has become a powerful way to understand the MAGA movement: many are not attracted to Trump in spite of his sadism but because of it.

This in turn helps explain why South Dakota governor Kristi Noem, who wants to be Trump’s vice-president, boasted in her bio about shooting her puppy Cricket. Perhaps Noem figured this would endear herself to the former president, who has a well-known dislike of dogs.

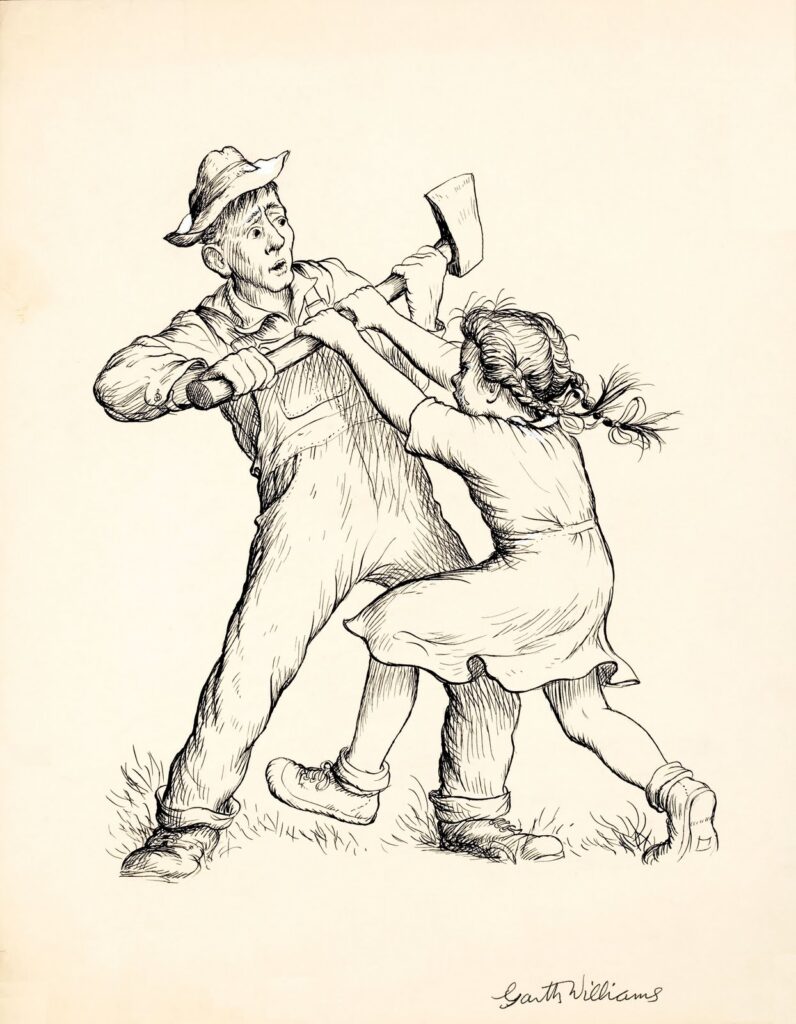

Noem grew up on a farm, where killing animals is sometimes necessary. Not that this makes such tasks necessarily easier. My wife talks about the challenge of killing chickens when she was growing up on a small southeastern Iowa farm. I’m also sure that I’m not the only child who was traumatized by the Garth Williams illustration in Charlotte’s Webb of Fern holding off her axe-wielding father as he goes after Wilbur, the runt of the litter.

E.B. White’s book is powerful in part because it acknowledges the stark reality at play in rural America. It’s a fact of life that farm-raised pigs do not have a spider advocate to save them from their destined end. Charlotte’s Web is noteworthy as a children’s book because it has the courage to grapple with life and death issues.

Sometimes dogs too must be put down, such as Old Yeller in Fred Gipson’s novel, who saves the family from a rabid wolf but contracts the illness in the process. There’s also the rabid dog in To Kill a Mockingbird, a foreshadowing of the “rabid” Bob Ewell, who assaults his daughter and blames an innocent Black man for it.

Perhaps most powerfully, there’s the tragic story of the sheepdog-in-training, young George, in Far from the Madding Crowd. Instead of rounding up the flock, George stampedes them over a cliff, rendering the kindly Gabriel Oak an instant pauper:

With a sensation of bodily faintness [Gabriel] advanced: at one point the rails were broken through, and there he saw the footprints of his ewes. The dog came up, licked his hand, and made signs implying that he expected some great reward for signal services rendered. Oak looked over the precipice. The ewes lay dead and dying at its foot—a heap of two hundred mangled carcasses, representing in their condition just now at least two hundred more.

Gabriel, we learn, is so humane that he feels “an arrant traitor to his defenseless sheep” when he has to turn one into mutton. After first feeling a deep pity for his decimated flock, he is then faced with the enormity of his loss:

It was a second to remember another phase of the matter. The sheep were not insured. All the savings of a frugal life had been dispersed at a blow; his hopes of being an independent farmer were laid low—possibly forever. Gabriel’s energies, patience, and industry had been so severely taxed during the years of his life between eighteen and eight-and-twenty, to reach his present stage of progress that no more seemed to be left in him. He leant down upon a rail, and covered his face with his hands.

In spite of his loss, however, he still feels for young George, who only thought he was doing his job:

As far as could be learnt it appeared that the poor young dog, still under the impression that since he was kept for running after sheep, the more he ran after them the better, …collected all the ewes into a corner, driven the timid creatures through the hedge, across the upper field, and by main force of worrying had given them momentum enough to break down a portion of the rotten railing, and so hurled them over the edge.

Hardy doesn’t hold back on the injustice of it all:

George’s son had done his work so thoroughly that he was considered too good a workman to live, and was, in fact, taken and tragically shot at twelve o’clock that same day—another instance of the untoward fate which so often attends dogs and other philosophers who follow out a train of reasoning to its logical conclusion, and attempt perfectly consistent conduct in a world made up so largely of compromise.

If Noem had killed Cricket in such a setting, she would be forgiven. In her book, however, she makes the killing personal:

“I hated that dog,” Noem writes, adding that Cricket tried to bite her, proving herself “untrainable”, “dangerous to anyone she came in contact with” and “less than worthless … as a hunting dog.”

Then, to further prove her ruthlessness, she writes about shooting an unruly goat immediately afterwards.

It’s not as though she didn’t have other options. One animal rights group laid them out.

“There’s no rational and plausible excuse for Noem shooting a juvenile dog for normal puppy-like behavior,” said a statement from Wayne Pacelle, president of Animal Wellness Action and the Center for a Humane Economy. “If she is unable to handle an animal, ask a family member or a neighbor to help. If training and socializing the dog doesn’t work, then give the dog to a more caring family or to a shelter for adoption.

Sometimes animals have to be put down, although even in seemingly clear instances there can be moral complications, as George Orwell makes clear in his essay “Shooting an Elephant.” But Noem, in a book designed as a campaign advertisement, is uninterested in nuance. She wants to show the MAGA faithful, and to show Donald Trump, that she is one mean motherf***er.

In other words, the cruelty is the point.