Thursday

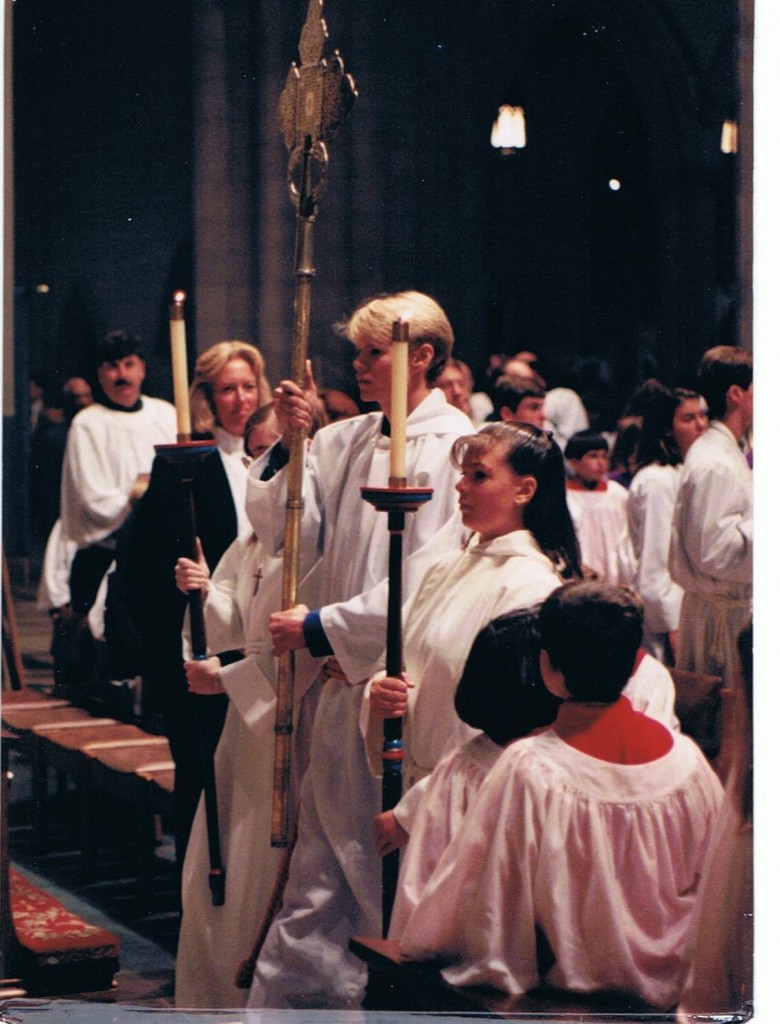

Today is the 20th anniversary of my eldest son’s death. While swimming in a normally safe spot in the St. Mary’s River, he was grabbed and pulled under by a rogue current, generated by an abnormally wet spring. He was a 21-year-old Religious Studies major at the time, and his death turned our world upside down.

I’ve written about how I turned to poetry to process his death. I particularly looked to elegies and for a while became obsessed with Tennyson’s In Memoriam. In the end, however, I chose for Justin’s gravestone a stanza from Shelley’s Adonais, written in memory of Keats. I imagined people sitting on the bench we installed, looking down at the spot where Justin drowned, and reading the following passage from stanza XLII:

He is made one with Nature: there is heard

His voice in all her music, from the moan

Of thunder, to the song of night's sweet bird;

He is a presence to be felt and known

In darkness and in light, from herb and stone…

I wanted people to imagine him present as they looked up at the trees and out over the water, and so it has transpired. For a long while people left sprigs of heather and small stones on the grave, but later these gave way to scallop shells from the beach. Children love the grave because they respond to the shells.

For today’s post, however, I choose a passage appearing earlier in the poem. Trying to make sense of Keats’s passing, Shelley notes the contrast between human death and nature’s eternal return. Every year at this time I too find my grief out of tune with the new growth and the vibrant animal life:

Ah, woe is me! Winter is come and gone,

But grief returns with the revolving year;

The airs and streams renew their joyous tone;

The ants, the bees, the swallows reappear;

Fresh leaves and flowers deck the dead Seasons' bier;

The amorous birds now pair in every brake,

And build their mossy homes in field and brere;

And the green lizard, and the golden snake,

Like unimprison'd flames, out of their trance awake.

Through wood and stream and field and hill and Ocean

A quickening life from the Earth's heart has burst

As it has ever done, with change and motion,

From the great morning of the world when first

God dawn'd on Chaos; in its stream immers'd,

The lamps of Heaven flash with a softer light;

All baser things pant with life's sacred thirst;

Diffuse themselves; and spend in love's delight,

The beauty and the joy of their renewed might.

Although the body decays, Shelley says in the next stanza that it is touched by Nature’s “spirit tender” and “exhales itself in flowers of gentle breath.” I love the shift from the celestial to the earthly, from stars to plant life. Elsewhere in the poem, Shelley associates poetry with the celestial, so astral splendor changing to flower fragrance hints at spirituality entering the world. “Nought we know dies,” Shelley concludes at this point in his exploration:

The leprous corpse, touch'd by this spirit tender,

Exhales itself in flowers of gentle breath;

Like incarnations of the stars, when splendor

Is chang'd to fragrance, they illumine death

And mock the merry worm that wakes beneath;

Nought we know, dies…

The poem has multiple shifts of tone, however, and doubts then arise. Humans, after all, are alone amongst nature’s creatures that know death, and death is “a most cold repose”:

Shall that alone which knows

Be as a sword consum'd before the sheath

By sightless lightning?—the intense atom glows

A moment, then is quench'd in a most cold repose.

Shelley may be drawing on the “Now let us praise famous men” passage from Ecclesiasticus in the next stanza, the one that reads,

And some there be, which have no memorial, who are perished as though they had never been, and are become as though they had never been born, and their children after them. (44:9)

Shelley is struck by how transient Keats’s qualities are. Often it is only our love for the dead that preserves them from oblivion, and the poet points out that our grief itself is transient. This line of thought leads him to the big questions: ”Whence are we, and why are we? Of what scene/The actors or spectators?” If existence is no more than an unending parade of mass death, then what’s the point?

Alas! that all we lov'd of him should be,

But for our grief, as if it had not been,

And grief itself be mortal! Woe is me!

Whence are we, and why are we? of what scene

The actors or spectators? Great and mean

Meet mass'd in death, who lends what life must borrow.

As long as skies are blue, and fields are green,

Evening must usher night, night urge the morrow,

Month follow month with woe, and year wake year to sorrow.

There are deliberate echoes here of Macbeth’s famous musings on the subject:

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

Shelley does not yield to such despair, however, and by the time he gets to the stanza I put on Justin’s stone, he is focusing on poetry. Keats is one with nature, not only in a biological sense but because “Ode to a Nightingale” has influenced how we hear “the song of night’s sweet bird.” That’s how “he is a portion of the loveliness/ Which once he made more lovely.”

Justin will not be remembered as Keats is, of course. Nevertheless, Shelley’s poem frames the experience of those who sit in the Trinity Church graveyard and think of those buried there. The dead become mingled with the beauty of the place. It’s possible to believe at such moments that

[t]he One remains, the many change and pass;

Heaven's light forever shines, Earth's shadows fly;

Life, like a dome of many-colour'd glass,

Stains the white radiance of Eternity,

Until Death tramples it to fragments.

I’ll cite one more passage as it reminds me of Justin, who was always smiling, always singing, and always engaged in spiritual search. Shelley writes of how “lofty thought lifts a young heart above its mortal lair” and declares,

The splendors of the firmament of time

May be eclips'd, but are extinguish'd not;

Like stars to their appointed height they climb,

And death is a low mist which cannot blot

The brightness it may veil.

Shelley is talking about great talents that died young, and while we’ll never know how high Justin would have soared—Shelley says of Keats that “he has outsoar’d the shadow of our night”–he too was a brightness that death cannot entirely blot. Or to cite Shelley’s concluding line, for me he is a star that “beacons from the abode where the Eternal are.”