Friday

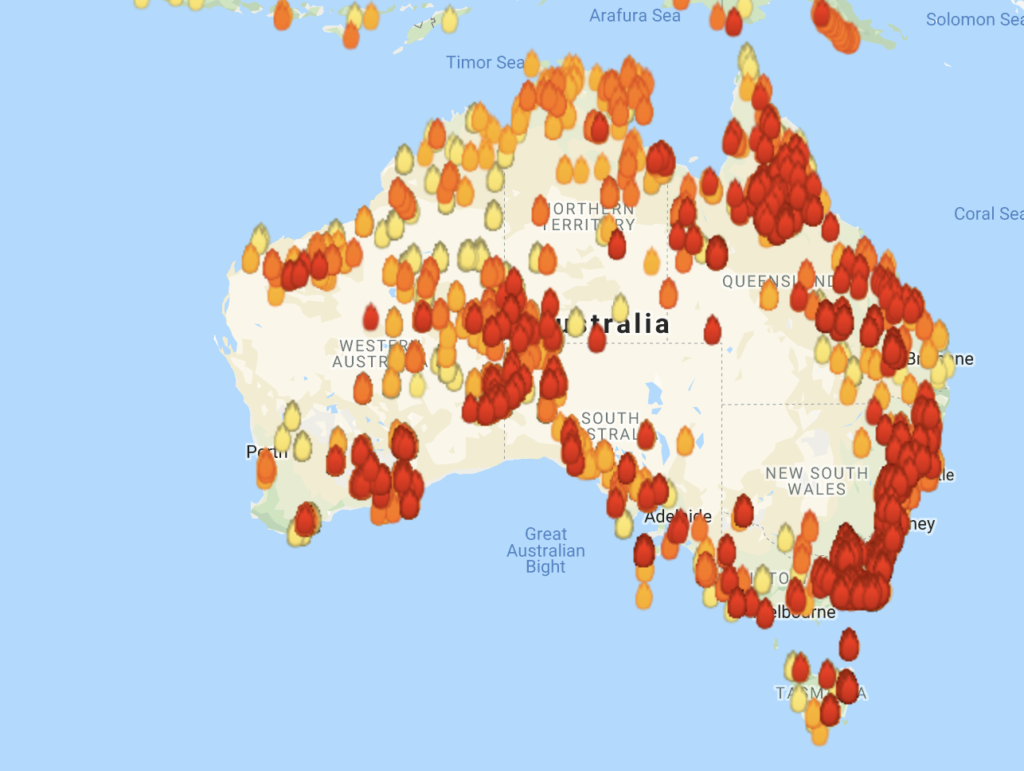

Given the fires that are devastating Australia, I’m updating a post I wrote five years ago citing Robert Frost’s “Fire and Ice.” From its ravaged coral reefs to its burning interior, Australia is showing itself to be one of the world’s climate change canaries.

“Some say the world will end in fire,/Some say in ice,” Robert Frost writes in his well-known poem, and it increasingly appears that everyone is right. Australia’s inferno follows terrifying reports of Greenland’s accelerating ice melt. According to National Geographic this past October,

Today, the Greenland ice sheet is losing mass about six times faster than it was just a few decades ago, whatever tenuous balance that existed before long since upended. Between 2005 and 2016, melt from the ice sheet was the single largest contributor to sea level rise worldwide, though Antarctica may overtake it soon.

Within the past 50 years, the ice sheet has already shed enough to add about half an inch of water to the world’s oceans, and that number is increasing precipitously as the planet heats. During this summer’s extreme heat wave that parked over Greenland for a week and turned over half its surface ice to slush, meltwater equivalent to over 4 million swimming pools sloughed into the ocean in a single day. Over the month of July, enough melt poured into the ocean to bump sea levels up by an easily measurable half a millimeter.

Frost, who may have Milton’s hot hell and Dante’s cold hell in mind, is writing about relationships, not climate change. As he sees it, the relationship is in trouble whether the partners are fiery passionate or icy cold. Fire is louder and more flamboyant, but the silent workings of cold can be just as deadly:

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

The poem is just as relevant to our current situation, however, where apocalypse is looking increasingly likely.

Speaking of apocalyptic accounts that get at our situation, here are two that I’ve cited in the past, one from The Iliad and one from C. S. Lewis’s Last Battle. I wrote the following last August about the burning of the Amazon rainforests:

My anger finds some articulation in a horrific scene in The Iliad. Because Hector has killed his dearest friend, Achilles reengages in the war and goes on a killing spree so bloody that the River Scamander reacts in horror. When Achilles clogs its channels with dead Trojans, it rises up in a giant wave and bears down on the Greek warrior.

Because Achilles is beloved by the Gods, however, the iron-working god Hephaistos enters the fray, and his technology is brought to bear. I think of the Amazon’s unparalleled biological diversity as I read what happens next:

Then against the river

Hephaistos turned his bright flame, and the elms

and tamarisks and willows burned away,

with all the clover, galingale, and rushes

plentiful along the winding streams.

Then eels and fish, in backwaters, in currents,

wriggled here and there at the scalding breath

of torrid blasts from the great smith, Hephaistos…

And further on:

[The river] spoke in steam, and his clear current seethed, the way a caldron whipped by a white-hot fire boils with a well-fed hog’s abundant fat that spatters all the rim, as dry split wood turns ash beneath it. So his currents, fanned by fire, seethed, and the river would not flow but came to a halt, tormented by the gale of fire from the heavenly smith, Hephaistos.

This isn’t the only time that Achilles is associated with devastating fire. In an earlier passage, Homer uses fire imagery to capture his slaughter:

A forest fire will rage

through deep glens of a mountain, crackling dry

from summer heat, and coppices blaze up

in every quarter as wind whips the flame:

so Akhilleus flashed to right and left

like a wild god, trampling the men he killed

and black earth ran with blood. As when a countryman

yokes oxen with broad brows to tread out barley

on a well-bedded threshing floor, and quickly

the grain is husked under the bellowing beasts:

The sharp-hooved horses of Akhilleus just so

crushed dead men and shields. His axle-tree

was splashed with blood, so was his chariot rail,

with drops thrown up by wheels and horses’ hooves.

And Peleus’ son kept riding for his glory,

staining his powerful arms with mire and blood.

Achilles may be Iliad’s hero, but Homer fully intends for us to experience the tragedy of what happens. Once the most humane of the Greeks, as Caroline Alexander points out in her superb book The War that Killed Achilles, Achilles has lost all perspective and grinds to dust everything that is human and sacred: Nature is ravaged, bodies are desecrated, and people’s hearts are torn apart. One can plausibly argue that The Iliad is the world’s greatest anti-war work as it exposes the colossal waste of armed conflict.

The war that today’s humans are waging against nature is occurring on an epic scale and is having epic consequences. Unlike in The Iliad, however, reactive nature will dole out consequences that even heavenly fire cannot resist. Our descendants will curse us for the world we have left them.

***

Now on to sea-level rise. Here’s the passage I cited from the last of the Narnia Chronicles in which C. S. Lewis rewrites the Book of Revelation:

At last something white—long, level line of whiteness that gleamed in the light of the standing stars—came moving towards them from the eastern end of the world. A widespread noise broke the silence: first a murmur then a rumble, then a roar. And now they could see what it was that was coming, and how fast it came. It was a foaming wall of water. The sea was rising. In that tree-less world you could see it very well. You could see all the rivers getting wider and the lakes getting larger, and separate lakes joining into one, and valleys turning into new lakes, and hills turning into islands, and then those islands vanishing. And the high moors to their left and the higher mountains to their right crumbled and slipped down with a roar and a splash into the mounting water; and the water came swirling up to the very threshold of the Doorway (but never passed it) so that the foam splashed about Aslan’s forefeet. All now was level water from where they stood to where the waters met the sky.

When fire and ice team up, we’re in trouble like we’ve never seen before. As a character tells Buffy the Vampire Slayer in the popular television series by that name,

When I saw you stop the world from, you know, ending, I just assumed that was a big week for you. It turns out I suddenly find myself needing to know the plural of apocalypse.

Previous posts on literature that cast light upon issues raised by climate change:

Many of my posts have been about climate change denial. For instance:

Kingsolver Explains Climate Denial — Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior includes a deep dive into why poor Appalachian whites don’t believe that climate change is happening.

Climate Scientists, Our Cassandras–Climate scientists must feel like Agamemnon’s Cassandra as they try to warn the world.

Civil War Battle, Image of Climate Denial – Ambrose Bierce’s famous short story “Chickamauga” helps us understand why people ignore the facts about our changing climate.

Donne’s Warning about Climate Change – Donne mentions the movement of the spheres in his poem “Valediction: Forbidding Mourning,” but they are distant, and he makes the important point that we only see the effects of nature that occur right before our eyes, not the larger patterns. Think of Senator James Inhofe bringing a snowball to the Senate to disprove global warming.

Tolstoy and Climate Change Denial – We can see that climate change denialists follow in the footsteps of the Moscow aristocrats in War and Peace, who can’t believe that Napoleon will take the city.

Out of Denial and into Responsibility – Jack Burden in Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men gives us a great description of the philosophy of denial, which he calls “idealism.” By the end of the novel, fortunately, he decides to face up to reality.

Obama: A Hard Rain’s A Gonna Fall – Poet Henry Vaughan decries fools who “prefer dark night before true light,” and Alexander Pope in The Dunciad goes after the dunces who turn their backs on science, intelligence, and logic.

GOP Denies a Giant Problem – For another instance of denial, it is hard to top Jonathan Swift’s Lilliputians, who refuse to believe that other men like Gulliver could exist. Their philosophers conclude that he must have dropped from the moon.

Haiyan, Climate Change, and King Lear – King Lear also closes his eyes to the family and political storms that he has triggered. His most trustworthy counselor advises him to “See better, Lear,” thereby earning banishment.

When American Fantasies Are Dangerous – In American Gods, Neil Gaiman gives us a great example of denial: southern slave owners refuse to acknowledge that there has been a successful slave rebellion in Haiti.

Melville and Climate Change Denial – Another instance of slave society denial occurs with Captain Delano in Melville’s fine novella Benito Cereno refusing to see the rebellion going on right before his eyes..

Some write about the grim future ahead:

Amazon Fires and the Fury of Achilles https://betterlivingthroughbeowulf.com/amazon-fires-and-the-fury-of-achilles/

Byron’s Climate Change Nightmare – Responding to a volcanic eruption that caused a year without summer, Byron imagined an end-of-the-world scenario.

Elemental Joy in California’s Wildfires? – Can it be possible that some people are actually reveling in the consequences of climate change?

Will Warm Days Never Cease — Classic poems like Keats’s “Ode to Autumn” suddenly look different as climate change has its way with us.

Still Falls the Rain – Hurricane Harvey, exacerbated by human-caused climate change–invites comparisons with the London blitzkrieg, as described by Edith Sitwell.

How Will the Future Judge Us for Trump? — Jane Hirshfield has a poem that gets us to look at ourselves from a future perspective, including what we did not do in the face of disaster.

Caves of Ice, Prophecies of War – Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” poem came to mind as I heard the catastrophic news about the breakup of arctic ice.

Neil Gaiman and the Pipeline Protests — Gaiman’s American Gods should us what will happen to us if we offend the local deities.

Our Children Will Reproach Us – Lucille Clifton shows us how our children will view us.

Climate Change, Fairies Fighting – Climate change, as described by Shakespeare in Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Climate Action Will Lead to Dystopia – Russell Hoban’s post-apocalyptic novel Riddley Walker is about nuclear holocaust, not climate change, but it captures the same disregard and contempt for future generations that climate denialists are exhibiting.

Hydrocarbons Unleash an Angry God – Euripides’s The Bacchae shows how nature responds when we try to impose our will upon it. The control freak King Pentheus is torn apart at the order of Dionysus.

This Is the Way the World Ends – Robert Frost’s poem “Fire and Ice” sounds as though it was written for climate change. Will the world end in fire or ice? How about both?

Will Californians Become the New Okies? – The droughts that climate change is visiting upon California (not to mention other parts of the world) bring to mind the ecological nightmare described by John Steinbeck in Grapes of Wrath.

The Mariner’s Advice to College Students – Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner can be read as an ecological parable—the arrogance that the mariner exhibits by shooting the albatross unleashes “life in death” upon the world.

Some authors provide useful advice for climate activists:

A Talk with a Cli-Fi Activist – An interview with Dan Bloom about the genre of “cli-fi” or climate fiction.

Kingsolver Tries to Save the Planet – Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior directly takes on the issue of climate change as it shows disruptions in the migratory patterns of monarch butterflies. Most usefully, Kingsolver shows various constituencies that must learn to talk to each other if we are to address the issues.

To Save the Planet, Scientists Must Protest — Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior shows why climate scientists cannot simply retreat into their labs.

Being Right on the Climate Is Not Enough – Along these lines, Ibsen’s Enemy of the People has important lessons for climate activists: if you want to change people’s minds, avoid self-righteousness.

Climate Change: Signs of Witchery – Leslie Marmon Silko, a Laguna Pueblo writer, vividly captures environmental devastation in her novel Ceremony but also has her protagonist discover a healthier way of living in the world.

Climate Hope Shines in Dark Times – Madeleine L’Engel has a wonderful Advent poem that I shared after the world gathered in Paris this past December to combat climate change. Despite the grim forecasts, we experienced a glimmer of hope.

And finally, if you are in the mood for light verse about the environment,here are a number of poems by my father, a deep lover of nature:

An ABC of Our Attack on the Earth

The River’s Blood Turned to Stone